Barriers and Facilitators to Integrating Gender-Affirming Care and HIV Prevention/Treatment in Illinois and Missouri

Formative Interviews with Implementation Practitioners

alithia zamantakis , Juan Pablo Zapata , Artur A.F.L.N. Queiroz , Valeria A. Donoso

Transgender people experience vast disparities in HIV prevalence, incidence, linkage to care, treatment, and prevention. Recent scholarship has highlighted that gender affirming care (GAC) may facilitate HIV treatment and HIV prevention. However, few researchers have examined how best to integrate these forms of care outside LGBT-focused clinics. Twelve interviews were conducted with key informants in community-based organizations, HIV clinics, and health departments in urban and rural Illinois and Missouri. Interviews were analyzed using a rapid qualitative analytic process, involving the production of analytic memos, coding of memos in NVivo using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, and production of matrices for within-site and cross-site comparison. Key informants were highly excited at the possibility of integrating gender affirming care and HIV services. They highlighted numerous barriers that need to be targeted, including local attitudes and conditions, equity-centeredness, provider capability, and policies and laws. They also highlighted barriers to HIV care alone for transgender patients, including transportation, cost, stigma, provider capability, and homelessness. While numerous barriers exist, provider and funder acceptability are high. Attending to the needs of trans patients may support efforts to end the HIV epidemic by increasing organizational adoption of evidence-based and equity-centered interventions.

- Volume (Issue)

- 3(3-4)

- Published

- December 15, 2024

- DOI

- 10.57814/f928-4976

- Copyright

- © 2024. The Authors. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

- Preferred Citation

- zamantakis, alithia, Juan Pablo Zapata, Juan Pablo, Queiroz, Artur A.F.L.N., Valeria A., Donoso. 2024. "Barriers and Facilitators to Integrating Gender-Affirming Care and HIV Prevention/Treatment in Illinois and Missouri: Formative Interviews with Implementation Practitioners ." Bulletin of Applied Transgender Studies 3 (3-4): 205-228. https://doi.org/10.57814/f928-4976

Trans people experience vast disparities in HIV prevalence, treatment, and prevention (Sullivan et al. 2021). In a recent survey of trans women in seven major US cities, 42% of participants were living with HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021). However, disaggregated by race, 61.9% of Black trans women surveyed were found to be living with HIV compared with just 17% of white trans women (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021). This disparity in HIV prevalence is only surpassed by the difference observed between cisgender men who have sex with men (MSM) and cisgender heterosexual individuals, highlighting a profound health inequity within the trans community (Sullivan et al. 2021). Transmasculine individuals have also been found to have an HIV prevalence of 2.8%, which, while significantly lower than trans women and cisgender MSM, is considerably higher than the national prevalence rate of 0.4% (Radix et al. 2022).

Trans people of all genders are less likely to be retained in HIV care and adherent to antiretroviral therapies (ART) than all people with HIV (Klein et al. 2020; Teti et al. 2019). Being retained in care is directly correlated to facilitating viral suppression, or the reduction of HIV in an individuals’ blood to non-detectable viral level (Mugavero et al. 2012; Tripathi et al. 2011). Viral suppression not only improves patient outcomes and quality of life but also prevents transmission of HIV (The Lancet HIV 2017; LeMessurier et al. 2018). Disparities in retention in care, ART adherence, and viral suppression may be mediated, in part, by anti-trans stigma, homelessness, incarceration, poverty, and other social determinants of health (SDOH), or the “material circumstances and psychosocial and behavioral characteristics” shaping individuals’ health outcomes and access to care before they become ill or step foot in a clinic (Illinois Department of Public Health 2024; Jain et al. 2023).

Research indicates that trans individuals exhibit lower rates of engagement with and adherence to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a preventative measure against HIV that includes either an oral pill or a bimonthly injection for those not infected with HIV (Downing et al. 2022; Reisner et al. 2021). This is even though trans people generally demonstrate a high awareness of PrEP and express significant interest in utilizing it (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021; Reisner et al. 2021). PrEP initiation is particularly low among Black and Latina trans women (Poteat et al. 2019). Reasons for this gap between awareness and uptake include the predominant marketing of PrEP to cisgender MSM, a prioritization of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) over HIV prevention methods, and fears of deportation and criminalization for undocumented trans women, among other structural barriers (Zamantakis et al. 2023).

Recent scholarship has demonstrated the positive effect of integrating gender-affirming care (GAC) into HIV treatment (Sevelius et al. 2014; Sevelius et al. 2022; Sevelius, Chakravarty, et al. 2021). Gender-affirming health care environments lead to healthcare empowerment for trans women of color. This sense of empowerment is a crucial factor in achieving viral suppression (Sevelius, Chakravarty, et al. 2021). While access to HRT has been identified as a facilitator of retention in HIV care and viral suppression (Sevelius et al. 2022), access to GAC may also serve as a potential facilitator of PrEP uptake and adherence (Connolly et al. 2020; Doan et al. 2022; Nieto et al. 2021; Restar et al. 2023; Sevelius et al. 2016; Sevelius, Glidden, et al. 2021; Starbuck et al. 2022; Zamantakis et al. 2023; Zamudio-Haas et al. 2023).

In March 2022, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) released a letter that encouraged Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program (Ryan White, henceforth) service providers to use available resources to implement GAC, including HRT and mental health services (Cheever 2021). Ryan White is considered a payer of last resort for HIV treatment, meaning if there are no other resources to fund the care, Ryan White will provide funding. Thus, Ryan White providers tend to see highly marginalized populations, such as Black and Latine communities, individuals living below the federal poverty line, and people who are either on public insurance or lack any insurance coverage at all (Health Resources and Services Administration 2023). While HRSA now expressly allows Ryan White funds to be used for GAC, clinics and community-based organizations may not have the tools, knowledge, or expertise to immediately integrate GAC and HIV treatment.

Implementation science (IS) provides the tools, frameworks, and methods to analyze how best to integrate GAC and HIV treatment/prevention in varying contexts. It identifies key determinants, such as barriers and facilitators, affecting the delivery and reception of services (Bauer et al. 2015; Bauer and Kirchner 2020). Furthermore, it devises implementation strategies, or processes, policies, trainings, and other tactics for provider, clinical, and systems-level modifications, aimed at overcoming these barriers and leveraging facilitators (E. K. Proctor et al. 2013). Implementation researchers intend to enhance the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and sustainment of evidence-based interventions (Glasgow et al. 1999; E. Proctor et al. 2011). Further, IS aims to close the seventeen-year gap between when a practice is found to be evidence-based and when it is implemented in real world settings (Morris et al. 2011), which is necessary to achieve the goals of the National Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative (Fauci 2013).

Our team decided to conduct this study in response to reviewer comments on a proposal we submitted for funding from the National Institutes of Health to expand research on this topic. The reviewer argued that a weakness of the proposal was a focus on Illinois where “trans people can access HIV prevention and care along with GAC.” They further argued that Illinois is a site of high access to GAC. At first glance, this could appear to be true. Illinois law protects patients and their parents from outside states from prosecution or extradition for seeking out GAC in Illinois (Gender-Affirming Care 2024). Illinois law further protects providers’ licenses for providing legal care, like GAC, even when such care is illegal in other states, and state initiatives, like the Transgender and Gender Diverse Wellness and Equity Program, provide additional state funding to health care organizations to expand access to GAC (Department of Human Services 2024; Wholesale Drug License-Various 2023).

However, laws do not guarantee the availability or accessibility of care. This is evident regarding disabled individuals’ access to care. Despite legal provisions requiring providers to make care accessible to disabled individuals, the CDC reports that 25% of do not have a “usual health care provider” and 25% have unmet health needs because of an inability to afford care (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024). Similarly, Illinois law allows residents to have an “X” gender marker on identification cards, yet implementation of this in practice has proven difficult, even years after the passage of this legislation (Gorner 2023). The actual enforcement and implementation of a law requires active and intentional attention to the barriers present for providers and organizations to carry out these changes.

Thus, we carried out formative key informant interviews with providers at HIV/AIDS-focused community-based organizations (CBOs), trans-focused CBOs, and Health Departments (HDs) in Illinois and Missouri to identify preliminary barriers to patient access of GAC and HIV services, identify barriers to provider and clinical level integration of GAC and HIV services, and understand the landscape of GAC access within these two states. This work will inform the next steps in developing implementation strategies to facilitate integration of GAC and HIV services.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured key informant interviews with providers in HIV/AIDS-focused CBOs, trans-focused CBOs, and one HD in Illinois and Missouri. The objective was to conduct formative research to understand patient, provider, and clinical-level barriers to accessing GAC, accessing HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment services, and integrating GAC and HIV services. Illinois and Missouri were selected as two priority-designated areas within the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative. While Illinois has state protections for trans healthcare, Missouri has attempted to pass or passed several bills preventing access to trans healthcare. The two states share a border, with nearly 100,000 vehicles crossing the Poplar Street Bridge connecting St. Louis, MO and East St. Louis, IL daily (Department of Transportation 2022). HIV prevalence in Cook County, IL is among the highest in the country, with 586 people per 100,000 living with HIV (Sullivan et al. 2020). While 60.9% of people living with HIV in Cook County were virally suppressed in 2021, only 53.9% of Black people living with HIV were virally suppressed compared to 73.8% of white people living with HIV (Sullivan et al. 2020). In Missouri, 252 people per 100,000 were living with HIV in 2021. Of the 13,103 living with HIV, 66.8% were virally suppressed, with disparities between Black/Latine and non-Latine white individuals living with HIV (Sullivan et al. 2020).

Sampling

While patients and providers both provide necessary input that is critical for the design and implementation of evidence-based interventions (EBIs), IS is particularly concerned with provider input, as these individuals have firsthand insight regarding how to deliver an intervention. Prior research mentioned above has identified a great desire by trans individuals for an integration of GAC and HIV treatment and/or HIV prevention. Thus, what is needed now is an understanding of how to make that possible in practice. Future research should attend to joint patient and provider perspectives of how best to integrate GAC and HIV treatment and/or HIV prevention in a way that is feasible for providers and accessible for patients.

We first compiled a list of all CBOs providing or linking trans and nonbinary individuals to GAC, HIV treatment, and/or HIV prevention within Illinois and Missouri, as well as a list of HDs across Missouri. For Illinois, we included a list of HDs who coordinate HIV treatment and prevention in “Care Connect” regions. Illinois HIV Care Connect functions as statewide care coordination within eight regions that cross the entire state. Providers refer patients to Care Connect where they are linked to HIV care and resources for SDOH (e.g., linkage to the Food Bank; Illinois Public Health Association 2024). We emailed organizations asking to speak with a member of high-level leadership to coordinate which provider had the greatest interaction with trans and nonbinary individuals and the greatest level of understanding of barriers to care for these populations. After two emails, we called organizations at three time points as follow-up recruitment. We received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval to carry out this research in July 2023 from Northwestern University.

Data Collection

Between July and December 2023, we carried out 12 key informant interviews. Interviews were conducted over Zoom, led by the first author, a PhD-level researcher with expertise in traditional and rapid qualitative analysis. The interview guide was informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Damschroder et al. 2022. CFIR is a compendium of implementation determinants, or barriers and facilitators to implementing an evidence-based intervention or practice. CFIR includes five domains: 1) innovation characteristics (e.g., barriers and facilitators related to GAC); 2) outer setting (i.e., contextual factors within the larger community, state, or nation that influence implementation, such as policy and financing); 3) inner setting (i.e., factors within the organization or clinic that may hinder or enable implementation); 4) individuals (i.e., do providers and patients have the capability, opportunity, and motivation to carry out implementation); and 5) process (i.e., what components of the implementation process are in place to facilitate implementation, such as data collection and analysis).

Interviews were recorded, and the interviewer took notes throughout the interview using a structured template based on the interview guide. Interviews lasted an average of 28 minutes, with a range of 23–62 minutes. Interview participants were compensated $100 for their participation.

Data Analysis

We used a rapid qualitative research process common within IS (Hamilton and Finley 2019; Mwamba et al. 2023; St. George et al. 2023). Rapid qualitative analysis, in comparison to traditional qualitative analyses (e.g., grounded theory), can be conducted within a much shorter time frame (40% less time) and with fewer costs due to eliminating the need for transcriptions and fewer person hours needed to complete the analysis (Nevedal et al. 2021). This shorter time frame does not eliminate the quality of the analysis. A comparison of both approaches to qualitative research has found both approaches to provide methodological rigor, in-depth analysis, and nuanced description, given the proper training of research team members (Nevedal et al. 2021). Rapid qualitative research, though, meets the demands of health services and implementation research, which aim to reduce the amount of time between which research is conducted and findings are translated into practice (Hamilton and Finley 2019). With this in mind, the interviewer refined the notes into an analytic memo within 36 hours of the interview, adding to notes already taken by returning to the recorded interview and compiling memos at the end of the interviews. Analytic memos were uploaded to NVivo software (Lumivero 2023) for data analysis and coded according to CFIR to produce matrices for within-site and cross-site comparison.

Results

Demographics

Key informants (KIs; N = 12) were roughly split between Illinois and Missouri, with slightly over half (n = 7) from Missouri (see Table 1). Most KIs (n = 7) were from metropolitan and rural areas outside Chicago and St. Louis. KIs were interviewed at HIV/AIDS-focused CBOs (n = 9), trans-focused CBOs (n = 2), and a health department in rural Illinois (n = 10). Most KIs were Black (n = 8), with four white KIs. Most were cisgender (n = 6 cisgender men; n = 3 cisgender women), with 3 trans KIs (n = 2 trans women; n = 1 nonbinary participant).

Table 1. Organizational Descriptions of Key Informants

| Informant | Type of Organization | Area |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | Chicago |

| 2 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | Chicago |

| 3 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | Rural Missouri |

| 4 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | St. Louis |

| 5 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | St. Louis |

| 6 | Health Department | Rural Illinois |

| 7 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | Rural Illinois |

| 8 | Transgender-focused CBO | Urban Missouri |

| 9 | Transgender-focused CBO | Urban Illinois |

| 10 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | Urban Missouri |

| 11 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | Urban Missouri |

| 12 | HIV/AIDS-focused CBO | St. Louis |

Note. Key informant demographics (i.e., race and gender) are not listed along with organizational descriptions to prevent identifiability. Urban Missouri and Illinois refer to urban and metropolitan areas outside Chicago and St. Louis. For anonymity, we have chosen to designate these simply as urban areas.

Determinants of Integration

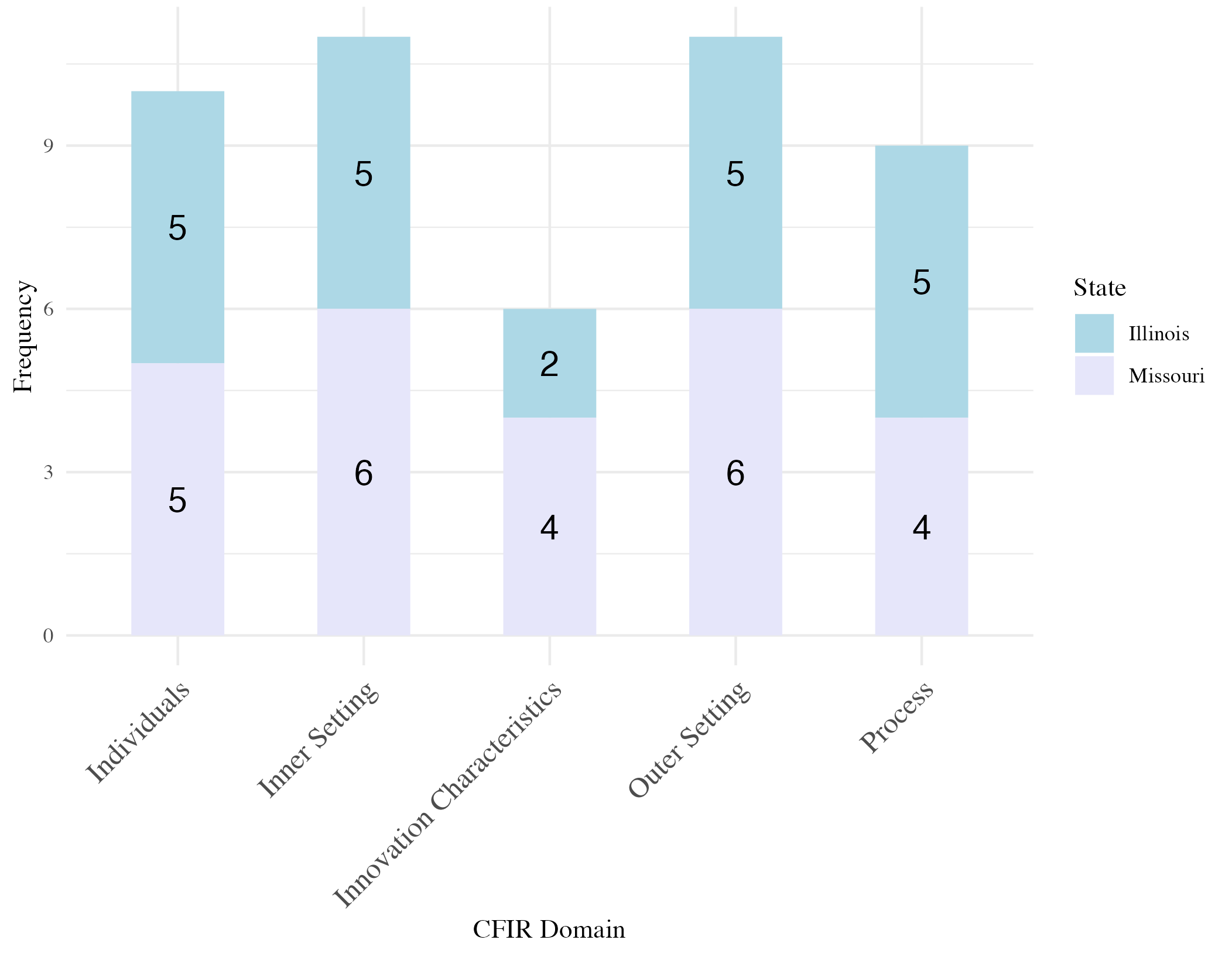

The most frequently mentioned determinants included local attitudes (n = 11; i.e., the sociocultural values and beliefs within the larger community), local conditions (n = 11; i.e., social, environmental, political, and economic factors within the community, state, and nation), equity-centeredness (n = 8; i.e., the value of providing equitable care to all patients within an organization or clinic), capability (n = 8; i.e., do providers have the psychological and physical skills necessary to integrate GAC and HIV services), and engaging (n = 8; i.e., engaging providers and patients in process of integrating services to facilitate successful implementation). The least mentioned included design quality and packaging (n = 1; i.e., how GAC and HIV services are designed and marketed), structural characteristics (n = 1; i.e., whether organizations have the physical, information technology, and work infrastructure necessary to integrate GAC and HIV services), relational connections (n = 1; i.e., how connected various departments are within the organization), communication (n = 1), culture (n = 1; i.e., the culture of the organization, how individuals work together, what they value), knowledge and beliefs about the innovation (n = 1; i.e., what do providers think about integrating GAC and HIV services), planning (n = 1; i.e., whether plans already exist to integrate GAC and HIV services), and reflecting and evaluating (n = 1; i.e., whether the organization has processes to collect and analyze data to determine how to successfully carry out implementation). There were no meaningful differences in how frequently different domains were mentioned by participants across Illinois and Missouri (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. CFIR domain by state

Interestingly, there were also no differences in domains mentioned by trans KIs and cisgender KIs. This may, in part, be due to the smaller sample size, as well as due to the predominance of Black KIs, who, like trans KIs, spoke from the viewpoint of both being a provider and a marginalized patient. Below, we elaborate on determinants mentioned by at least one-third of KIs (see Figure 2 for a visual rendering of these determinants).

Figure 2. Determinants mentioned by three or more key informants

Innovation Characteristics

Relative advantage. Within the innovation characteristics domain, only relative advantage was mentioned by one-third or more KIs (n = 5). Relative advantage refers to whether integrating GAC and HIV services is advantageous over other existing practices within the organization or clinic. Three of the KIs who mentioned relative advantage highlighted the advantage of integrating GAC and HIV services on health outcomes. One KI from rural Missouri explained:

If they’re [trans patients] getting their trans care at the same space, they’re much more likely to stay engaged in care, on meds, and suppressed. It’s nice that we can have those conversations with our patients about who should be on PrEP and make sure they’re getting those services in addition to their trans care. Makes it easier to wrap around all those services.

By bundling care, clinics would be able to increase access for trans patients and increase engagement in care. Other KIs highlighted, for example, that many trans patients experience barriers to transportation. Having to find rides, pay for car shares, or take public transit long distances decreases the likelihood that patients will make multiple trips for health care, they argued. If patients could access these forms of care at the same place, then prioritization of GAC over HIV services would no longer be a barrier.

Two KIs also highlighted that providing GAC and HIV services in the same space increases “comfort” for patients to receive their PrEP or HIV care. Clinics offering GAC would have received training in providing such care and staff would have increased familiarity with trans patients. Thus, KIs felt patients would not have to worry about bias or discrimination within the clinic. A KI from St. Louis, Missouri argued, “More girls would get tested and on PrEP. ‘This place is helping me [as a patient] with this, why not go ahead and do it?’”

Finally, two KIs also highlighted that integrating GAC and HIV services would serve to not only increase engagement in care, ART adherence, and PrEP uptake but would also increase GAC access. KIs explained the distance patients travel to receive GAC. For patients in rural Southern Missouri, accessing many forms of GAC may result in a 3-hour trip to St. Louis. For patients in Kansas City, it may be a 4-hour trip to St. Louis. For patients in parts of Illinois outside Chicago, the trip is upwards of 2 hours. One KI in upstate Illinois regularly drives trans patients to Chicago (a 2-hour distance) to access HRT. While two hours may seem a shorter distance, she explained that, for working, poor, and homeless individuals she serves, a 2-hour trip requires time off work, a vehicle, money for gas, and money for food, in addition to the costs of health care. Thus, integrating GAC and HIV prevention/treatment would be a “huge relief,” as the upstate Illinois KI stated “right now, we are spending a lot of time and money on taking people to appointments. This [traveling] is not effective.”

Outer Setting

Local attitudes. Eleven KIs discussed local attitudes as a barrier to accessing HIV care. Each of these KIs discussed this as “stigma,” homophobia, transphobia, or racism. For example, one KI in Chicago discussed a patient who told her about their experience attempting to get STI testing at a local clinic. The patient had to partially disrobe for the provider’s assessment, and the provider mocked them for their genitals not matching their identity. Another KI in rural Missouri highlighted:

I think it’s just important that there are safe spaces for any patient, especially folks who are really a minority among other patients and who you know, I have patients all the time who come in and say I talked to my doctor about trans care and they “fired me” or they wouldn’t give me a new appointment and so we live in an area of the country where there is very little experience dealing with sexual and gender minorities.

In addition to these experiences of discrimination, KIs also discussed the role that internalized stigma and a lack of education plays. When patients are told they are living with HIV, they experience shame and fear. As one KI stated, “Once you have your status, who’s going to accept you?” Internalized stigma coupled with medical transphobia emerged as blockades that need to be addressed to increase access for trans patients.

Local conditions. Eleven KIs also discussed the role of local conditions as barriers to accessing care. This includes a lack of housing for trans individuals and safety for them if they are living at home. For some KIs, substance use was the largest barrier in the communities they serve due to high rates of substance abuse. Others raised issues of poverty, high rates of mental illness, and a lack of familial and social support. These SDOH impede patients’ ability to prioritize HIV care, let alone other forms of care. Substance use and mental illness result in difficulties remembering to take one’s PrEP or ART daily and to attend medical appointments.

Others also highlighted the role of transportation in rural and urban areas. For those in urban areas, the availability of buses and subways does not necessarily dismantle the barrier, as trans individuals may not feel safe on public transit due to fears of discrimination and violence. One KI in Kansas City elaborated:

We may give a bus ticket to someone but taking the bus may not be safe for someone, so we’ve had to advocate for Ubers or cab rides. In the long run, it saves money because someone in care saves the system a lot of money in the long run. Some trans people don’t use public transit at all. If they don’t have a ride, they aren’t going.

For those in rural areas, distance served as the mechanism through which transportation became a barrier. One KI in rural Illinois serves an area of nineteen counties. As a result,

Some of them travel 150 miles round trip to get here. That’s one of the reasons we’re trying to develop more community partnerships because we know being centrally located has some advantages. We’re just a couple miles from [university] but we know that there are a lot of care prevention and service deserts in these rural areas that have communities anywhere from 300-3,000 residents so getting here or even having to come here to get any of those services we offer…that needs to be something that they can access in their community.

Thus, a lack of access in rural areas and safe transportation in urban areas presented barriers to trans patients seeking out care. Another KI in North Illinois highlighted that they have nearby providers of GAC, but these providers are located immediately across the border in Wisconsin. As most of their patients were on Medicaid or Medicare, they had to instead travel several hours to Chicago to receive care, because state insurance only pays for care in Illinois.

Finally, political conditions exacerbated disparities in access to care in Missouri. In 2023, Missouri passed legislation criminalizing the provision of GAC to minors. Minors already receiving care are allowed to continue receiving care, but new patients cannot be served. The KI explained:

We can accept no new minor patients. They’d have to go four hours to Illinois to get any care. Previous legal proposals wanted people to be in mental therapy for 18 months and any mental illness would disqualify you from gender affirming health care. So, the care providers were instructed they couldn’t do it any longer, and they were told they would no longer be allowed to provide any. Currently we are the only one in [region of] Missouri [providing this care]. Our service area is 21 counties.

This KI further highlighted that they are the only provider of PrEP in this same service area. Thus, patients lack access to GAC and HIV prevention.

Partners and connections. KIs discussed the critical necessity of partnerships and connections with other providers, health care organizations, and hospital systems. As one KI from Chicago stated, “Partnerships are essential to ensuring under resourced organizations and HDs can succeed.” These partnerships took various forms. KIs in rural and urban areas of Missouri provided linkage-to-care for gender affirming surgeries, HRT, and even to clinics that provide Botox and other fillers to ensure use of sterile syringes and surgical grade Botox. While these partnerships allowed organizations to overcome gaps in services they provide, referring patients out again relies on transportation, which KIs identified as a key barrier.

Policies and laws. Policies and laws were highlighted as barriers and facilitators by six key KIs. In Missouri, the policy environment hindered integration of GAC and HIV prevention/treatment. In August 2023, Missouri banned puberty blockers, hormone replacement therapy and gender affirming surgery for minors. The same legislation barred state Medicaid from covering any form of GAC for people of all ages and prohibited access to GAC in all prisons, jails, and correctional centers. Prior to the law’s passage, previous legal proposals included requirements for trans patients to receive mental therapy for at least 18 months prior to receiving care and would disqualify any patient from GAC if they were diagnosed with a mental illness. The law’s passage and the previous wording of attempted legislation led to many providers closing their facilities due to fear and due to diminished access to patients.

In Illinois, the policy environment functioned as a facilitator, as Illinois passed legislation in 2021 protecting providers from legal attacks for providing care to patients traveling from states with GAC bans. However, KIs highlighted the need to continue working with policymakers to increase access to care and to ensure all individuals impacted by HIV would have access to transitional, supportive, and permanent housing. A KI in Chicago highlighted the difficulty in making legal and administrative changes:

With legislative work, there’s a clear path, with administrative [work], it’s like who’s the right person in the right bureau to champion this? With any policy, the implementation part inevitably takes longer and is more challenging than getting through the hurdles of getting the words on the paper approved.

Some policy changes, like revoking legislation banning GAC, require legislative changes. However, others, like integrating care, may require administrative changes (e.g., altering funding schemes, developing standardized protocols). Further, the policy change must be implemented and enforced to ensure it has its intended impact.

Another KI in Southern Illinois reported frustration with the lack of access to care despite a supportive policy environment. He shared:

I think there are a lot of people in St. Louis that would love the state support that we have in Illinois, but they do have the masses and the industry [to reach people]. I wish that we had, I think if we had more industry in southern Illinois, we would be able to grow our population centers and attract people from other parts of the Midwest and really be able to have more points of access for GAC for individuals.

Thus, a facilitative policy environment in combination with a supportive economy and growing population may be necessary to achieve successful integration of GAC and HIV prevention/treatment.

Financing. Seven KIs discussed the need for increased funds from local, state, and federal agencies to expand resources. Some KIs highlighted that they were already experiencing decreases in funding from Ryan White, forcing them to find other revenue streams. One KI in rural Missouri, though, discussed this as an opportunity, explaining:

There’s a need. No one else is doing it. As a Ryan White clinic providing care to folks living with HIV, our funding is 10% less than when we were taking care of 200 PLWH and now we have 800. Without increasing our services and providing additional funding streams, the organization won’t survive. I’m pushing to expand services, pushing us to become a look alike and then FQHC to bring in the income we need to continue to exist as an organization and thereby provide services to folks who can’t otherwise get this type of care.

Expanding services can provide new mechanisms to fund an organization, ensuring the survival of CBOs. However, this may need to happen in tandem with expanding insurance coverage. One KI in Southern Illinois noted, “If the insurance doesn’t have robust coverage for folks, then that’s going to drive them to underground practices. Buying hormones off the dark web and don’t know if they’re safe or not.” When states like Missouri ban Medicaid from covering GAC, it may not result in all trans people no longer accessing GAC; instead, it may lead some to seek out care from less safe sources.

Performance measurement pressure. Performance measurement pressure, or pressure from contract requirements, reporting, and other “formal mechanisms of performance accountability” (Raghavan et al. 2008) was only mentioned by KIs outside Chicago. Only one KI in Illinois discussed performance measurement pressure. While performance measurement pressure can force CBOs to increase the volume of care they provide, it can also result in barriers to implementation. A KI in Southern Illinois highlighted:

A lot of the organizations that serve similar populations, they’re often funded by the same grants, so they can become ultracompetitive, so it can become a hinderance to them working together and better. Most of us here just want everyone to succeed but underneath that, there’s still this sense of I don’t want to give away any potential reimbursements because that’s money I need as well.

This sort of pressure and competition can hinder the development of partnerships and connections, as CBOs need to be reimbursed by their HD or other sources of funding to continue providing care. However, collaboration could prove more fruitful to develop new services, expand resources, and facilitate referrals.

Inner Setting

Equity-centeredness. Within the inner setting, equity-centeredness, or a clinical culture that values equity, justice, and the provision of care to marginalized populations, was the most mentioned determinant (n = 8). KIs discussed this in terms of 1) developing an equitable culture for staff and 2) centering equity as the guiding force of integrating GAC and HIV prevention/treatment. The two themes are interrelated, as who staffs an organization and how staff are treated and valued shapes the clinical care patients receive. In terms of developing an equitable culture for staff, KIs highlighted work they had accomplished to develop racial equity committees, carry out compensation reports, bring in specialty consultants, rehaul compensation, and reconfigure insurance benefits and job descriptions. Doing so provided staff and providers with the resources needed to carry out their roles.

KIs further highlighted the need to move beyond cultural responsiveness training. Rather than only providing trainings to staff on how to work with and treat marginalized populations, they spoke of a need to target the barriers patients experience in accessing care. This included ensuring patients have access to housing, food, work, and other resources to address SDOH. One KI referenced Cornel West’s (2001) concept of providing services that do have a “non-market value.” He stated, “They may not bring a profit or revenue, but they build up the community. This is what is needed to prevent HIV.”

Providing equity-centered care also requires investing in trans communities. A KI in St. Louis noted:

A lot of the times the people in the trans community like to go here, because they know the girls who are here. We do have trans girls that work here. I wouldn’t want to go somewhere I wouldn’t be understood. So, because we go through a lot of the same issues [regardless of status], we still go through the same stigma, the same pain. They want to go somewhere they are understood.

Hiring trans people, developing their skills, and fostering an inclusive and equitable organization brings in clients, as it shows to them that they will be respected and affirmed.

Ultimately, KIs felt that eradicating barriers and developing equity-centered organizations would translate into improved health outcomes. One KI from Kansas City explained, “If people feel like there are space that genuinely care for them, genuinely want to see them living, and thriving, and vivant, then they are more likely to keep up their care.” Integrating GAC and HIV prevention and treatment, hiring trans people, and supporting the staff at an organization were seen as critical to carrying out their mission to end HIV.

Relative priority. Six KIs discussed the relative priority of integrating GAC and HIV prevention/treatment in comparison to other ongoing work. All six highlighted integrating GAC into their HIV services as a high priority. They explained that their goal is to end HIV and provide care to individuals living with HIV. Integrating GAC into their HIV services aligned with this goal, as they viewed this process as increasing access, uptake, and adherence. KIs reported a desire to integrate GAC, explaining they just need the resources or connections to do so.

Staffing. Many KIs reported staffing as one of the main barriers, in addition to funding (n = 8). KIs’ organizations already provided bundled services to mitigate the impact of SDOH. These organizations had food pantries, clothing closets, showering stations, primary care, HIV care, patient navigation, and other services to address these needs. Most already had primary care providers or nurses within the organization; therefore, the need became training staff to provide trans health.

Two KIs spoke of the need to hire clinicians to carry out this work. One KI in St. Louis noted, “We have the space to do it. We would just need the clinicians to do it…and the funding support to do it. If we could get the clinicians and the funding support to do it, it’s a no-brainer.” Integrating GAC and HIV services was viewed as highly compatible with their existing infrastructure, mission, and the needs of the populations they serve. Training clinicians, in addition to funding, became the barrier.

Individuals

Capability. Eight KIs identified provider capability as an additional barrier. Capability refers to both physical capability (i.e., having the skills to implement the intervention) and psychological capability (i.e., having the knowledge and training to do so). When KIs discussed capability, they primarily focused on psychological capability regarding the provision of GAC, as well as psychological capability to provide equitable services.

Regarding GAC, one KI in Northern Illinois discussed barriers to patients accessing care at pharmacies. Even if patients have providers who will prescribe HRT, some pharmacy technicians may not understand why or how to fill these prescriptions. Thus, there is a need for training not only of providers within a clinic but also of all medical personnel who may be involved in the provision of care. Another KI in Chicago also discussed the need for training, noting that all staff in a clinic need to be trained. While some may focus on just training medical doctors, this KI emphasized that nurse practitioners, physician’s assistants, receptionists, administrative staff, and administrators all need to be trained to understand the necessity and priority of GAC.

Regarding the provision of trans-inclusive care, KIs spoke to barriers within HIV clinics broadly, as well as barriers within HIV clinics providing GAC. One KI in rural Missouri explained:

Educating the staff is kind of the biggest barrier and making sure that people are comfortable working with that population. Not everyone is and we’ve lost staff because of it. When we’re looking to hire people, it’s difficult, we have an intensive interview process where people are confronted with scenarios about trans folks, actively psychotic folks, actively injecting drug users, so that weeds people out of the application process.

The KI described the importance of this application process and training staff to ensure all patients can access the care they need. However, this process also results in a loss of potential applicants. Thus, larger cultural shifts and greater training around sexual and gender diversity in educational institutions may be needed as an upstream intervention to increase the cultural competence of the workforce at large.

Finally, while some providers may already be integrating GAC and HIV services, this does not ensure patients have access to competent care. One KI in Southern Illinois elucidated this:

I know a lot of providers who are starting to get into hormone therapy or GAC because they’re starting to see more money come into it through Medicare or Medicaid but they’re not culturally competent so they could still be doing harm to folks. That is probably the biggest barrier. A lack of culturally intelligent services and service providers.

Integrating GAC and HIV services will require training on the provision of various forms of GAC, including HRT, but will also include training on best practices vis-a-vis providing equitable care to trans people to ensure that care is accessible to patients.

Opportunity. One-third of KIs (n = 4) also spoke of patient opportunity as a barrier. Opportunity includes physical opportunity (i.e., having the resources needed to access care) and social opportunity (i.e., having the social support from family, friends, and the larger community to access care). The KIs who spoke of this were mainly in Missouri, with one in Southern Illinois. In discussing opportunity, patients primarily spoke of physical opportunity, highlighting barriers, such as transportation, knowledge of where to get tested, and awareness of existing resources and where “safe” clinics are located. However, they also described barriers related to social opportunity, including repeated discussion of stigma (both HIV stigma and anti-trans discrimination) as critical barriers impeding access to care. KIs also highlighted mental health as an additional barrier that needs greater attention within clinics and organizations. Finally, they discussed the role of staff and providers in limiting patients’ access to care. For example, a KI in Kansas City who serves homeless and low-income patients stated:

I don’t want a physician looking at someone who’s been on the street for four days, like ‘You’ve got this stench about you.’ Can we drive them to our comprehensive building and work with them to get showered and groomed. They may not have access, so let’s provide the fucking access.

Thus, providers’ capability, as discussed in the previous section, limits patients’ opportunity. Provider training increases capacity to implement this type of care and expands patient access to care.

Process

Assessing needs. KIs (n = 4) discussed assessing the needs of patients as a facilitator to providing new sources of care. One KI discussed how they built out new services based on conversations with patients:

We put together HRT kits for people who are engaged in transitioning and hormones with intramuscular syringes, gauze, Band-Aids, and alcohol. We did that because, for folks who are transitioning or are on hormones, they say, “I can get my hormones covered by insurance but can’t get the rest covered so I don’t have access to those.” We built that specifically on the feedback of the trans folks who engage in our services."

By soliciting feedback and listening to the needs of patients, their CBO developed a resource that filled specific gaps in care. While patients on insurance may be able to access GAC, they may not have access to specific items, like syringes, associated with that care.

Engaging. Finally, eight KIs reported the need to engage trans patients in developing new services. They highlighted that it is not enough to develop resources and organizations addressing patients’ needs. The patients themselves must be involved as leaders and subject matter experts. For example, a KI in Chicago quoted author adrienne marie brown (2017), stating:

All organizing is science fiction because we’re creating the world that we want to see. So that is the essence of how to be successful to me in the policy arena, because why are you doing this if the people who are impacted are not leading the way? How do you even know if this is what they want? So, I have no problem stepping back. I like to curate the space and then do what’s necessary to nudge conversation and help people feel comfortable and I think that has led to—actually—I know that has led to us being super successful.

Providers and administrators may understand the technical and medical aspects of providing care, but for that care to be patient-centered, accessible, and impactful, it must include the very patients it aims to service. Integrating GAC and HIV prevention/treatment necessitates the involvement of trans patients in research and implementation.

Discussion

Trans individuals face a disproportionately high impact from the HIV epidemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021; Sherwood et al. 2021; Sullivan et al. 2021). Despite this, the integration of GAC—which has been shown to have a potentially lifesaving effect on the health of trans people (Lee et al. 2024; Stoehr et al. 2022)—into standard HIV prevention and care protocols is still lacking. This study aimed to explore the determinants influencing the implementation of GAC in clinics offering HIV services across two states and among various providers, aiming to enhance GAC integration in these environments. We identified determinant across several domains: the inner setting, the outer setting, characteristics of individuals, and aspects of health equity, which include culturally relevant factors, the clinical encounter, and the societal backdrop. Notably, our research is among the first to assess these determinants within the primary spaces frequented for HIV services, providing important insights for the incorporation of GAC.

As noted in the introduction, we conducted this study in response to grant reviewer comments that there is already high access to HIV prevention and GAC in places like Illinois. While that may be true in clinics based in Chicago, our KIs highlighted that it is not true across the board in Illinois. Our KIs spoke of the burden of transporting clients to and from Chicago to access GAC. While telemedicine is increasingly an option for patients in rural communities, there remain barriers for homeless populations and those without insurance, which many of our KIs serve. Further, despite differences in cultural and political climates between Illinois and Missouri, the barriers and facilitators KIs identified were largely consistent across borders. This elucidates a need for increased attention to access to GAC and HIV care in “blue” states and otherwise. It is important to note, though, that differences do exist between the two states. Integration of GAC and HIV prevention/treatment will require policy changes in Missouri, as it is illegal for providers to prescribe minors puberty blockers or HRT (Missouri Save Adolescents from Experimentation [SAFE] Act 2023). The same Missouri law also prohibits the state’s Medicaid program from covering GAC and prevents individuals who are incarcerated from accessing GAC. Thus, researchers will need to partner with community advocates and organizers to overturn legislation currently preventing trans individuals from accessing lifesaving care.

Further, it is necessary to note the role that movement across states plays regarding health care access and policy barriers. Individuals do not live stationary lives, remaining in one state or another. Instead, the modern economy and policy environment often require individuals to move across states and regions on a frequent basis. The passage of anti-trans health care legislation also provides further impetus for movement across states. In the wake of anti-trans legislation across the nation, including in Iowa, Missouri, Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, and Arkansas—all states surrounding or near Illinois—patients and their families have begun flocking to Illinois as a “safe haven” for medically necessary care (Henderson 2023; Lubbers 2023; Sfondeles 2024). While there is not available data detailing HIV prevalence among those fleeing to Illinois to maintain access to care, we can presume many of them either require access to HIV prevention or HIV treatment.

Despite these policy barriers, KIs across both states displayed a high level of acceptability of integrating GAC and HIV prevention/treatment. Their acceptability was based on the provision of equity-centered care and diversifying services offered in their organizations. Future researchers should attend to the development of implementation strategies (i.e., methods of targeting organizational and provider behavior and knowledge) and structural interventions to target policy. Implementation strategies like trainings on how to provide HRT, hiring trans staff, and developing mechanisms to cover or bill for GAC services may help to facilitate the integration of GAC and HIV prevention/treatment. Structural interventions like policy changes and increasing access to transportation will be needed to enable integration of GAC and HIV prevention/treatment in states like Missouri but will also help trans patients access services in all states across the country.

Our findings should be considered with the following limitations. Our study only involved twelve key informants, limiting generalizability. Our sample exhibits wide geographic variability, with the 12 KIs spanning both states, ranging from small, rural areas to dense, urban cities. Further, our KIs had a high level of variability in terms of their purview regarding implementation of HIV care and GAC. Thus, while our sample included individuals with a high level of knowledge on their settings, it was not a homogenous sample. Finally, we only conducted interviews with providers and funders. No interviews were conducted with patients as the focus of this study was on determinants of integrating HIV care and GAC. Future research should attend to how best to integrate these two forms of care in ways that are feasible for providers and accessible to patients. Despite these limitations, this study provides formative data for future researchers developing implementation strategies to integrate GAC and HIV prevention/treatment. Our next steps include conducting surveys and interviews with clinics, providers, and patients to develop implementation strategies and adjunctive interventions to integrate these two forms of care.

Conclusion

Integrating GAC and HIV prevention/treatment can increase uptake of and adherence to HIV prevention and treatment interventions. However, further research is needed to understand how best to integrate these two forms of care. Our research identified barriers and facilitators to accessing GAC and HIV prevention/treatment, as well as critical barriers to integrating these two forms of care. While numerous barriers exist, provider and funder acceptability are high, suggesting a need to develop implementation strategies to increase organizational capacity for integration. Attending to the needs of trans patients may support efforts to end the HIV epidemic in the U.S. by increasing organizational adoption of evidence-based and equity-centered interventions.

References

Bauer, Mark S., Laura Damschroder, Hildi Hagedorn, Jeffrey Smith, and Amy M. Kilbourne. 2015. “An Introduction to Implementation Science for the Non-Specialist.” BMC Psychology 3 (1): 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9.

Bauer, Mark S., and JoAnn Kirchner. 2020. “Implementation Science: What Is It and Why Should I Care?” Psychiatry Research 283: 112376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.025.

brown, adrienne marie. 2017. Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds. Chico, CA: AK Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. HIV Infection, Risk, Prevention, and Testing Behaviors Among Transgender Women: National HIV Behavioral Surveillance, 7 U.S. Cities, 2019–2020. HIV Surveillance Special Report 27. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. “Disability Impacts All of Us.” Disability and Health. https://www.cdc.gov/disability-and-health/articles-documents/disability-impacts-all-of-us-infographic.html.

Cheever, Laura W. 2021. Gender Affirming Care in the RWHAP. https://ryanwhite.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ryanwhite/hiv-care/gender-affirming-care-rwhap.pdf.

Connolly, Maureen D., Doreen N. Dankerlui, Tony Eljallad, Isadore Dodard-Friedman, Amy Tang, and Christine L. M. Joseph. 2020. “Outcomes of a PrEP Demonstration Project with LGBTQ Youth in a Community-Based Clinic Setting with Integrated Gender-Affirming Care.” Transgender Health 5 (2): 75–79. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0069.

Damschroder, Laura J., Caitlin M. Reardon, Marilla A. Opra Widerquist, and Julie Lowery. 2022. “The Updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Based on User Feedback.” Implementation Science 17 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0.

Department of Human Services. 2024. Transgender/Gender Diverse (TGD) Wellness and Equity Program. Illinois Catalog of State Financial Assistance. https://omb.illinois.gov/public/gata/csfa/Program.aspx?csfa=3227.

Department of Transportation. 2022. 2022 Illinois Travel Statistics. State of Illinois Department of Transportation: Office of Planning and Programming. https://idot.illinois.gov/content/dam/soi/en/web/idot/documents/transportation-system/reports/opp/travel-stats/2022-its-original-website.pdf.

Doan, Anh H., Chau M. H. Vu, Thu T. Nguyen, Kimberly E. Green, Hoang T. T. Phan, Rena Janamnuaysook, Bao N. Vu, Thanh M. Le, Khang Q. Do, Tham T. Tran, Trang M. Ngo, Lopa Basu, Long K. Tran, and Zoe Humeau. 2022. “Caring for the Whole Person: Transgender‐Competent HIV Pre‐Exposure Prophylaxis as Part of Integrated Primary Healthcare Services in Vietnam.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 25 (S5). https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25996.

Downing, Jae, Kimberly Yee, and Jae M. Sevelius. 2022. “PrEP Use and Adherence Among Transgender Patients.” AIDS and Behavior 26 (4): 1251–1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03482-8.

Fauci, Anthony S. 2013. “Ending the HIV/AIDS Pandemic: Research and Implementation.” JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 62: 55. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/01.qai.0000429247.62652.fd.

Gender-Affirming Care, HB5586, Illinois General Assembly 103 (2024).

Glasgow, Russell E., Thomas M. Vogt, and Shawn M. Boles. 1999. “Evaluating the Public Health Impact of Health Promotion Interventions: The RE-AIM Framework.” American Journal of Public Health 89 (9): 1322–1327. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.89.9.1322.

Gorner, Jeremy. 2023. “State Struggles to Implement 2019 Law That Allows ‘X’ Gender on IDs for Nonbinary Residents.” Chicago Tribune, July 10. https://www.chicagotribune.com/2023/07/10/state-struggles-to-implement-2019-law-that-allows-x-gender-on-ids-for-nonbinary-residents/.

Hamilton, Alison B., and Erin P. Finley. 2019. “Qualitative Methods in Implementation Research: An Introduction.” Psychiatry Research 280: 112516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112516.

Health Resources and Services Administration. 2023. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program: Annual Data Report. https://ryanwhite.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ryanwhite/data/rwhap-annual-client-level-data-report-2022.pdf.

Henderson, Own. 2023. “Providers Say Illinois Set to Become Haven for Gender-Affirming Care.” Illinois Public Media, May 11. https://will.illinois.edu/studentnewsroom/story/providers-say-illinois-should-prepare-to-be-haven-for-gender-affirming-care.

Illinois Department of Public Health. 2024. Understanding Social Determinants of Health. https://dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/life-stages-populations/infant-mortality/toolkit/understanding-sdoh.html.

Illinois Public Health Association. 2024. HIV Care Connect Regions. Illinois HIV Care Connect. https://hivcareconnect.com/hiv-care-connect-regions/.

Jain, Jennifer P., Miranda Hill, Kristi E. Gamarel, Glenn-Milo Santos, Mallory O. Johnson, Torsten B. Neilands, Samantha E. Dilworth, Cathy J. Reback, and Jae Sevelius. 2023. “Socio-Ecological Barriers to Viral Suppression Among Transgender Women Living with HIV in San Francisco and Los Angeles, California.” AIDS and Behavior 27 (8): 2523–2534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-023-03979-4.

Klein, Pamela W., Demetrios Psihopaidas, Jessica Xavier, and Tacy M. Cohen. 2020. “HIV-Related Outcome Disparities between Transgender Women Living with HIV and Cisgender People Living with HIV Served by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program: A Retrospective Study.” PLoS Medicine 17 (5): e1003125. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003125.

Lee, Min Kyung, Yuehwern Yih, Deanna R. Willis, Janine M. Fogel, and James D. Fortenberry. 2024. “The Impact of Gender Affirming Medical Care During Adolescence on Adult Health Outcomes Among Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals in the United States: The Role of State-Level Policy Stigma.” LGBT Health 11 (2): 111–21. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2022.0334.

LeMessurier, Jennifer, Gregory Traversy, Olivia Varsaneux, Makenzie Weekes, Marc T. Avey, Oscar Niragira, Robert Gervais, Gordon Guyatt, and Rachel Rodin. 2018. “Risk of Sexual Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus with Antiretroviral Therapy, Suppressed Viral Load and Condom Use: A Systematic Review.” CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal 190 (46): E1350–E1360. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.180311.

Lubbers, Max. 2023. “Illinois Becomes Magnet for Transgender Students Seeking Protections in School, Health Care.” Chalkbeat Chicago, August 29, 2023. https://www.chalkbeat.org/chicago/2023/8/29/23849555/transgender-laws-youth-florida-desantis-schools-education-illinois-lgbtq.

Lumivero. 2023. NVivo (Version 14) [Computer software]. www.lumivero.com.

Missouri Save Adolescents from Experimentation (SAFE) Act. 2023. Missouri Senate Bill 49, 236, 164. https://www.senate.mo.gov/23info/BTS_Web/Bill.aspx?SessionType=R&BillID=44407.

Morris, Zoe S., Steven Wooding, and Jonathan Grant. 2011. “The Answer Is 17 Years, What Is the Question: Understanding Time Lags in Translational Research.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 104 (12): 510–20. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110180.

Mugavero, Michael J., K Rivet Amico, Andrew O. Westfall, Heidi M. Crane, Anne Zinski, James H. Willig, Julia C. Dombrowski, Wynne E. Norton, James L. Raper, Mari M. Kitahata, and Michael S. Saag. 2012. “Early Retention in HIV Care and Viral Load Suppression: Implications for a Test and Treat Approach to HIV Prevention.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 59 (1): 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e318236f7d2.

Mwamba, Chanda, Laura K. Beres, Njekwa Mukamba, Lazarus Jere, Marksman Foloko, Kasapo Lumbo, Kombatende Sikombe, Sandra Simbeza, Aaloke Mody, Jake M. Pry, Charles B. Holmes, Izukanji Sikazwe, Carolyn Bolton Moore, Katerina Christopoulos, Anjali Sharma, and Elvin H. Geng. 2023. “Provider Perspectives on Patient-Centredness: Participatory Formative Research and Rapid Analysis Methods to Inform the Design and Implementation of a Facility-Based HIV Care Improvement Intervention in Zambia.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 26 (Suppl 1): e26114. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.26114.

Nevedal, Andrea L., Caitlin M. Reardon, Marilla A. Opra Widerquist, George L. Jackson, Sarah L. Cutrona, Brandolyn S. White, and Laura J. Damschroder. 2021. “Rapid versus Traditional Qualitative Analysis Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR).” Implementation Science 16: 67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-021-01111-5.

Nieto, Omar, Anne E. Fehrenbacher, Alejandra Cabral, Amanda Landrian, and Ronald A. Brooks. 2021. “Barriers and Motivators to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Uptake Among Black and Latina Transgender Women in Los Angeles: Perspectives of Current PrEP Users.” AIDS Care 33 (2): 244–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2020.1769835.

Poteat, Tonia, Andrea Wirtz, Mannat Malik, Erin Cooney, Christopher Cannon, W David Hardy, Renata Arrington-Sanders, Maren Lujan, and Thespina Yamanis. 2019. “A Gap Between Willingness and Uptake: Findings from Mixed Methods Research on HIV Prevention among Black and Latina Transgender Women.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 82 (2): 131–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002112.

Proctor, Enola K., Byron J. Powell, and J. Curtis McMillen. 2013. “Implementation Strategies: Recommendations for Specifying and Reporting.” Implementation Science 8 (1): 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139.

Proctor, Enola, Hiie Silmere, Ramesh Raghavan, Peter Hovmand, Greg Aarons, Alicia Bunger, Richard Griffey, and Melissa Hensley. 2011. “Outcomes for Implementation Research: Conceptual Distinctions, Measurement Challenges, and Research Agenda.” Administration and Policy in Mental Health 38 (2): 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7.

Radix, Asa E., Elaine L. Larson, Alexander B. Harris, and Mary Ann Chiasson. 2022. “HIV Prevalence among Transmasculine Individuals at a New York City Community Health Centre: A Cross-Sectional Study.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 25 (Suppl 5): e25981. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25981.

Raghavan, Ramesh, Charlotte L. Bright, and Amy L. Shadoin. 2008. “Toward a Policy Ecology of Implementation of Evidence-Based Practices in Public Mental Health Settings.” Implementation Science 3 (1): 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-3-26.

Reisner, Sari L., Chiara S. Moore, Andrew Asquith, Dana J. Pardee, and Kenneth H. Mayer. 2021. “The Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Cascade in At-Risk Transgender Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States.” LGBT Health 8 (2): 116–24. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2020.0232.

Restar, Arjee, Brian J. Minalga, Ma. Irene Quilantang, Tyler Adamson, Emerson Dusic, Leigh-Ann van der Merwe, Greg Millet, Danvic Rosadiño, Tanya Laguing, Elle Lett, Avery Everhart, Gregory Phillips II, Rena Janamnuaysook, Pich Seekaew, Kellan Baker, Florence Ashley, Jeffrey Wickersham, Stephaun E. Wallace, Don Operario, and Kristi E. Gamarel. 2023. “Mapping Community-Engaged Implementation Strategies with Transgender Scientists, Stakeholders, and Trans-Led Community Organizations.” Current HIV/AIDS Reports 20 (3): 160–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-023-00656-y.

Sevelius, Jae M., Deepalika Chakravarty, Torsten B. Neilands, JoAnne Keatley, Starley B. Shade, Mallory O. Johnson, and Greg Rebchook. 2021. “Evidence for the Model of Gender Affirmation: The Role of Gender Affirmation and Healthcare Empowerment in Viral Suppression Among Transgender Women of Color Living with HIV.” AIDS and Behavior 25 (Suppl 1): 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02544-2.

Sevelius, Jae M., Samantha E. Dilworth, Cathy J. Reback, Deepalika Chakravarty, Danielle Castro, Mallory O. Johnson, Breonna McCree, Akira Jackson, Raymond P. Mata, and Torsten B. Neilands. 2022. “Randomized Controlled Trial of Healthy Divas: A Gender-Affirming, Peer-Delivered Intervention to Improve HIV Care Engagement Among Transgender Women Living With HIV.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 90 (5): 508–16. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000003014.

Sevelius, Jae M., David V. Glidden, Madeline Deutsch, Layla Welborn, Alejandro Contreras, Arianna Salinas, Luz Venegas, and Robert M. Grant. 2021. “Uptake, Retention, and Adherence to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in TRIUMPH: A Peer-Led PrEP Demonstration Project for Transgender Communities in Oakland and Sacramento, California.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 88 (1): S27–S38. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0000000000002808.

Sevelius, Jae M., JoAnne Keatley, Nikki Calma, and Emily Arnold. 2016. “‘I Am Not a Man’: Trans-Specific Barriers and Facilitators to PrEP Acceptability Among Transgender Women.” Global Public Health 11 (7–8): 1060–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2016.1154085.

Sevelius, Jae M., Enzo Patouhas, JoAnne G. Keatley, and Mallory O. Johnson. 2014. “Barriers and Facilitators to Engagement and Retention in Care Among Transgender Women Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 47 (1): 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9565-8.

Sfondeles, Tina. 2024. “Illinois a Blue Haven for Gender Affirming Care, but Advocates Say Housing, Safety Still a Concern.” WBEZ Chicago, June 21, 2024. https://www.wbez.org/springfield/2024/06/21/illinois-general-assembly-lgbtq-legislation-gender-affirming-care-housing-safety.

Sherwood, Jennifer, Elise Lankiewicz, Erika Castellanos, Naomhán O’Connor, Liesl Theron, and Arjee Restar. 2021. “Assessing Inclusion of Trans People in HIV National Strategic Plans: A Review of 60 High HIV Prevalence Countries.” Journal of the International AIDS Society 24 (11): e25837. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25837.

St. George, Sara M, Audrey R. Harkness, Carlos E. Rodriguez-Diaz, Elliott R. Weinstein, Vanina Pavia, and Alison B. Hamilton. 2023. “Applying Rapid Qualitative Analysis for Health Equity: Lessons Learned Using ‘EARS’ With Latino Communities.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22: 160940692311649. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069231164938.

Starbuck, Lila, Sarit A. Golub, Augustus Klein, Alexander B. Harris, Amiyah Guerra, Christopher Rincon, and Asa E. Radix. 2022. “Transgender Women and Preexposure Prophylaxis Care: High Preexposure Prophylaxis Adherence in a Real-World Health Care Setting in New York City.” JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 90 (1): 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002915.

Stoehr, Jenna Rose, Alireza Hamidian Jahromi, Ezra Leigh Hunter, and Loren S. Schechter. 2022. “Telemedicine for Gender-Affirming Medical and Surgical Care: A Systematic Review and Call-to-Action.” Transgender Health 7 (2): 117–26. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0136.

Sullivan, Patrick S., Anna Satcher Johnson, Elizabeth S. Pembleton, Rob Stephenson, Amy C. Justice, Keri N. Althoff, Heather Bradley, Amanda D. Castel, Alexandra M. Oster, Eli S. Rosenberg, Kenneth H. Mayer, and Chris Beyrer. 2021. “Epidemiology of HIV in the USA: Epidemic Burden, Inequities, Contexts, and Responses.” The Lancet 397 (10279): 1095–1106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00395-0.

Sullivan, Patrick S., Cory Woodyat, Chelsea Koski, Elizabeth Pembleton, Pema McGuiness, Jennifer Taussig, Alexandra Ricca, Nicole Luisi, Eve Mokotoff, Nanette Benbow, Amanda D. Castel, Ann N. Do, Ronald O. Valdiserri, Heather Bradley, Chandni Jaggi, Daniel O'Farrell, Rebecca Filipowicz, Aaron J. Siegler, James Curran, Travis H. Sanchez. 2020. “A Data Visualization and Dissemination Resource to Support HIV Prevention and Care at the Local Level: Analysis and Uses of the AIDSVu Public Data Resource.” JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 22 (10). https://doi.org/10.2196/23173.

Teti, Michelle, L.A. Bauerband, and Claire Altman. 2019. “Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People Living with HIV: Findings from the 2015 U.S. Trans Survey.” Transgender Health 4 (1): 262–69. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2019.0050.

The Lancet HIV. 2017. “U=U Taking off in 2017.” The Lancet HIV 4 (11): e475. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30183-2.

Tripathi, Avnish, Eren Youmans, James J. Gibson, and Wayne A. Duffus. 2011. “The Impact of Retention in Early HIV Medical Care on Viro-Immunological Parameters and Survival: A Statewide Study.” AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses 27 (7): 751–58. https://doi.org/10.1089/AID.2010.0268.

West, Cornel. 2001. “The Moral Obligations of Living in a Democratic Society.” In The Good Citizen, edited By David Batstone and Eduardo Mendieta, 5–12. New York: Routledge.

Wholesale Drug License-Various. 2023. HB4664, Illinois General Assembly 102.

zamantakis, alithia, Dennis H. Li, Nanette Benbow, Justin D. Smith, and Brian Mustanski. 2023. “Determinants of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Implementation in Transgender Populations: A Qualitative Scoping Review.” AIDS and Behavior 27 (5): 1600–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-022-03943-8.

Zamudio-Haas, Sophia, Kim Koester, Luz Venegas, Ariana Salinas, Cinthya Herrera, Luis Gutierrez-Mock, Layla Welborn, Madeline B. Deutsch, and Jae Sevelius. 2023. “‘Entre Nosotras:’ A Qualitative Study of a Peer-Led PrEP Project for Transgender Latinas.” BMC Health Services Research 23: 1013. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09707-x.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank each of the participants for their assistance with this work. The authors also wish to thank the Qualitative Working Group at Northwestern University’s Institute for Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing and Department of Medical Social Sciences for providing access to NVivo software. This work was funded by a training grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH130325). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The sponsors had no involvement in the conduct of the research or the preparation of the article.