The Impact of Sociopolitical Events on Transgender People in the US

L. Zachary DuBois , Jae A. Puckett , Sarah F. Price , Kelsi Kuehn , Brenna Lash , Tian Walker , Natalie R. Holt , Allura L. Ralston , T. Zachary Huit , Makinna Miles , Sage Volk , A. Capannola , Clover Tipton , Debra A. Hope , Richard Mocarski , Robert-Paul Juster

Marginalization experienced by transgender and gender diverse (trans) people exerts negative effects on health. However, few studies examine how trans people respond to events reflecting structural stigma or anti-trans sentiment and the sociopolitical contexts in which they occur. This study examined how trans people (N = 158) residing in Michigan, Nebraska, Oregon, and Tennessee responded to specific sociopolitical events and their impacts on health and well-being. Baseline data were collected Fall 2019–Spring 2020, followed by monthly surveys for a year. Current analyses include baseline data and one monthly survey. At baseline, participants reflected on their responses to the 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump and a 2018 memo leak with negative implications for trans people’s lives. Participants reported decreased positive experiences (e.g., hopefulness) and increased negative experiences (e.g., fear) after these events. Additionally, 80.2% of participants reported increased hate speech following the 2016 election. During one of the monthly surveys, we found variability in participants’ responses to the 2020 presidential election. Perhaps due to backlash, 31.3% of participants reported increased hate speech, with participants of color reporting additional negative impacts. These findings contextualize experiences of trans people, highlighting how marginalization and exposure to minority stressors are shaped by structural-level stigma.

- Volume (Issue)

- 2(1-2)

- Published

- June 30, 2023

- DOI

- 10.57814/sdx3-7y41

- Copyright

- © 2023. The Authors. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

- Preferred Citation

- DuBois, L. Zachary, Puckett, Jae A., Price, Sarah F., Kuehn, Kelsi, Lash, Brenna, Walker, Tian, Holt, Natalie R., Allura L., Ralston, Huit, T. Zachary, Miles, Makinna, Volk, Sage, Capannola, A., Tipton, Clover, Hope, Debra A., Mocarski, Richard, Juster, Robert-Paul. 2023. "The Impact of Sociopolitical Events on Transgender People in the US." Bulletin of Applied Transgender Studies 2 (1-2): 1-26. https://doi.org/10.57814/sdx3-7y41

Since former President Donald Trump’s election in 2016, there has been a marked and on-going increase in anti-trans rhetoric and legislation that negatively impacts transgender and gender diverse (trans) people throughout the United States (Conron et al. 2022). The lives of trans people are directly impacted, for example, by political policies and practices including state-level legislation banning trans youth from accessing gender affirming care (Conron et al. 2022; e.g., HB 1557, 2022 Leg. [Fla. 2022]) and a proliferation of laws banning trans athletes from participating in sports (e.g., SB 1046, 55th Leg. [Ariz. 2022]) reflecting aspects of structural stigma. Trans people are also positively impacted by policies and practices at the federal level, for example, providing antidiscrimination protections based on gender identity and/or sexual orientation (2022 Executive Order 14075, “Advancing Equality for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans-Gender, Queer, and Intersex Individuals”). Nonetheless, despite the steady increase of trans visibility in the media and cultural recognition of trans identities in recent years, trans people are continuously faced with backlash, systemic discrimination, and erasure.

The ongoing societal debates targeting trans people’s rights and very existence also reflect the social and political climates within which trans people live day-to-day. As such, these broader sociopolitical contexts, as well as positive and negative events (e.g., legislation, elections), have impacts on health and well-being (Kuper, Cooper, and Mooney 2022). Anti-trans stigma within these contexts contributes to further marginalization of trans people, including heightened verbal and physical violence (Feinberg, Branton, and Martinez-Ebers 2019).

These experiences of stigmatization, discrimination, and violence also have adverse effects on the mental and physical health of trans people (Bockting et al. 2013; Hughto, Reisner, and Pachankis 2015; Gonzalez, Ramirez, and Galupo 2018; Link and Phelan 2006; Breslow et al. 2015). The current study adds descriptive data to help further our understanding of how sociopolitical contexts and events associated with structural stigma impact health and well-being. We examined how key societal events impacted the health and well-being of trans people living in four states in the US. These events included the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections, and the October 2018 memo leak during Trump’s administration that threatened trans exclusion by rigidly redefining sex and gender at the federal level as “a biological, immutable condition determined by genitalia at birth” (Green, Brenner, and Pear 2018, 1).

Understanding Stigma and Gender Marginalization Stress

Stigma occurs in multiple, overlapping ways and is increasingly recognized as an important social determinant of health and driver of population health disparities for trans people, as well as other marginalized groups (Hatzenbuehler 2009; Hughto, Reisner, and Pachankis 2015; King, Hughto, and Operario 2020). Building on sociological understandings of stereotypes and norms within sociocultural contexts (Goffman 1963), stigma refers to the systematic process by which people become socially discredited because they hold characteristics deemed somehow unacceptable, resulting in reduced access to resources and power (Brewis and Wutich 2020; Link and Phelan 2014; 2001). The minority stress model, sometimes referred to as marginalization stress, builds upon these frameworks to highlight how stigma and inequality impact sexual and gender minority populations specifically (Brooks 1981; Hendricks and Testa 2012; Meyer 2003; 2013; Puckett et al. 2020; Price, Puckett, and Mocarski 2021). The minority stress model details how distal stressors, such as discrimination, impact mental health and well-being, including via proximal stressors (e.g., internalized stigma). Although a helpful model, research that recognizes the broader sociopolitical context of systemic issues lags behind research on anti-trans stigma at the interpersonal or individual level (King, Hughto, and Operario 2020). Recognizing the structural factors that drive distal and proximal stressors provides a necessary analysis of power, privilege, and systemic factors that are key to understanding health disparities for this marginalized community.

Socioecological frameworks enable recognition of different levels of stigma. These include individual (individual behaviors), interpersonal (community interactions), or structural (laws, policies, and institutional practices) levels and further our understanding of how these interact with one another (Bronfenbrenner 1977; Hughto, Reisner, and Pachankis 2015). Research with trans people increasingly shows that structural factors shape individual experiences of stigma and marginalization. Puckett and colleagues’ (2022a) expansion of the socioecological model to trans people’s experiences of marginalization found that participants experienced a range of sociopolitical stressors. For example, the 2016 presidential election of Donald Trump resulted in heightened vigilance and fear in the daily lives of trans people. Similarly, DuBois and Juster’s (2022) extension of this model to trans people found participant levels of embodied stress (i.e., allostatic load) and mental health were significantly impacted by their perception of the sociopolitical climate in which they lived. By drawing these connections between systemic factors, individual experience, and health, research can reveal avenues for addressing structural inequities rather than placing the responsibility solely on the individual to adapt and manage inequities.

Impacts of Anti-Trans Rhetoric and Policies

Anti-trans political rhetoric and discourse often rests on the assertion that trans identities are somehow immoral (Haider-Markel et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2017; Vanaman and Chapman 2020). This morality-based discourse and related legislation directly encourages anti-trans public sentiment by deceptively suggesting that trans people pose a threat (e.g., legislation proposed to “protect” children; Conron et al. 2022). Previous research on morality politics and disgust-driven public policy implementation demonstrates how these public discourses directly lead to political policy and how policy proposals and enactment then influence public discourse (Haider-Markel et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2017; Vanaman and Chapman 2020). As these policies are disguised within arguments of “morality,” the stigma and discrimination therein become increasingly insidious.

As anti-trans sentiment and political policy continue to propagate in the US, trans people likewise continue to experience increased levels of discrimination and violence, with clear impacts on mental health, including increased levels of anxiety, depression, and vigilance (Gonzalez, Ramirez, and Galupo 2018; Price, Puckett, and Mocarski 2021; Puckett et al. 2022a; Veldhuis et al. 2018). Intersecting forms of stigma and oppression, including racism, white supremacy, cissexism, and transmisogyny, are also occurring across multiple levels, negatively impacting trans people, particularly trans women of color (Arayasirikul and Wilson 2019; Collins 2015; K. Crenshaw 1989; 1991; Serano 2016; Smart et al. 2022). Several studies have been published over the last 8 years examining the specific effects of the 2016 US presidential election and the co-occurring discriminatory political discourse on the mental health of marginalized people. For instance, in their study on marginalization stress and coping, Price and colleagues (2021) found that the increased anti-trans political discourse throughout the 2016 US presidential election led to increased experiences of stigma, stress, anxiety, and expectations of discrimination. Trump rallies have been recognized as contributing directly to escalations in hate speech and hate crimes targeting marginalized populations throughout the United States (Feinberg, Branton, and Martinez-Ebers 2019; Warren-Gordon and Rhineberger 2021). These documented incidents of hate and hostility continue to reinforce cycles of marginalization stress as they inflict fear of violence and discrimination on marginalized people (Meyer 2003; 2013; Puckett et al. 2020; Puckett et al. 2022a, b).

Similarly, Veldhuis and colleagues (2018) analyzed the impact of anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex (LBGTQI+) policies surrounding the 2016 presidential election (such as the marriage equality act and potential rollbacks on Obama-era protections for LBGTQI+ people) on the health and well-being of sexual minority women, transgender, and/or nonbinary individuals. In their study, they also found that participants reported increased feelings of fear, anxiety, depression, and vigilance surrounding their personal safety in response to the discourse surrounding the 2016 election. Participants in that study accurately anticipated the increase in normalization and propagation of anti-LBGTQI+ discrimination on a systemic level, as more and more of these anti-LBGTQI+ bills were introduced and implemented nationwide (Veldhuis et al. 2018). Discriminatory discourses and policies continue to spread throughout the US political system. These take a toll on the health and safety of LBGTQI+ people both physically and psychologically.

The Trans Resilience and Health Study

The Trans Resilience and Health Study aimed to elucidate the impacts of sociopolitical contexts and key events on trans people’s health, well-being, and resilience. The study enrolled a diverse sample of trans people residing in four states in the US (Michigan, Nebraska, Oregon, and Tennessee), which vary in legislative protections as well as levels and types of support available for trans people (Movement Advancement Project 2022). Baseline data were collected Fall 2019–Spring 2020, followed by a year of monthly surveys.

Analyses presented here draw on data from baseline and one of the monthly surveys to detail descriptive data about participant experiences of three key events that reflect structural-level factors and inequalities: 1) the 2016 US presidential election (Donald Trump versus Hillary Clinton); 2) the 2018 memo leak which occurred in October 2018 during the Trump administration and suggested a potential, narrow re-definition of both gender and sex as biological and immutable based on genitalia at birth (Green, Brenner, and Pear 2018); and 3) the 2020 US presidential election (Donald Trump versus Joe Biden).

Methods

Participants

There were 158 participants across Oregon (n = 45; 28.5%), Michigan (n = 39; 24.7%), Tennessee (n = 39; 24.7%), and Nebraska (n = 35; 22.2%). Participants were 19–70 years old at time of enrollment (M = 33.06; SD = 12.88). In terms of gender, 27.2% of participants identified as trans men/men, 26% as trans women/women, and the remaining participants identified with terms like genderqueer, nonbinary, and others. The sample was 30.4% people of color and 69% white. For a summary of sample characteristics, see Table 1.

Procedures

Participants were recruited through in-person and virtual outreach to community organizations, snowball sampling, and social media. Potential participants completed an online screener which included basic demographic items. The screener data was then used to target recruitment to maximize diversity regarding gender identities, race/ethnicities, and age across each of the 4 states in the study. Eligibility criteria required participants to be at least 19 years of age (the age of majority in Nebraska), trans identified, and living in Michigan, Nebraska, Oregon, or Tennessee. As described above, these states were selected because they reflect variation in sociopolitical climates, legislative protections, and types and levels of support available for trans people (Movement Advancement Project 2022).

Once enrolled, participants completed a baseline in-person, semi-structured interview focused on their experiences in their state of residence, their reflections on recent sociopolitical events, and the topic of resilience. Participants then completed a series of questionnaires and surveys along with the collection of biomarker samples to assess embodied stress effects and health (for elaboration of these approaches see DuBois et al. 2021). After baseline data collection ended, participants completed monthly online surveys for 12 months (April 2020–March 2021), followed by a final semi-structured virtual interview and in-person collection of biomarker samples assessing health and allostatic load. Retention was high throughout the 12 months of follow-up ranging from 118 (74.68%) to 147 (93.04%) participants completing each monthly survey, with an average retention rate of 83.76% across the 12 months. Data analyzed here focuses on baseline data and one of the monthly surveys focused on the specific events described below. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Oregon. Participants provided their informed consent during the baseline visit.

Measures

Demographics

Participants completed a series of questions, including items assessing age, gender identity, race and/or ethnicity, and rural, urban, or suburban residence. See Table 1 for sample characteristics, including response options.

Table 1. Sample Demographics (N = 158)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender Identity | |

| Trans man | 37 (23.4%) |

| Trans woman | 32 (20.3%) |

| Genderqueer | 16 (10.1%) |

| Non-binary | 40 (25.3%) |

| Agender | 3 (1.9%) |

| Androgyne | 1 (0.6%) |

| Genderfluid | 2 (1.3%) |

| Woman | 9 (5.7%) |

| Man | 6 (3.8%) |

| Bigender | 2 (1.3%) |

| Not listed | 9 (5.7%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

| Race or Ethnicity | |

| Black or African American | 8 (5.1%) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 (1.3%) |

| Asian | 6 (3.8%) |

| Latinx | 6 (3.8%) |

| White | 109 (69%) |

| Not listed | 1 (0.6%) |

| Multiracial/Multiethnic | 26 (16.5%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| Bisexual | 44 (27.8%) |

| Gay | 23 (14.6%) |

| Lesbian | 20 (12.7%) |

| Queer | 83 (52.5%) |

| Asexual | 16 (10.1%) |

| Pansexual | 60 (38%) |

| Heterosexual/Straight | 8 (5.1%) |

| Not Listed | 8 (5.1%) |

| Employment | |

| Employed Full-time | 69 (43.7%) |

| Employed Part-time | 48 (30.4%) |

| Full-time Student | 38 (24.1%) |

| Part-time Student | 6 (3.8%) |

| Unable to work for health reasons | 16 (10.1%) |

| Unemployed | 11 (7%) |

| Other | 13 (8.2%) |

| Residential Area | |

| Rural | 26 (16.6%) |

| Suburban | 55 (35%) |

| Urban | 76 (48.4%) |

| Education Level | |

| High school graduate – high school diploma or equivalent (i.e., GED) | 14 (8.9%) |

| Some college credit, but less than 1 year | 8 (5.1%) |

| Technical or vocational school degree | 5 (3.2%) |

| One or more years of college, no degree | 42 (26.6%) |

| Associate degree | 18 (11.4%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 52 (32.9%) |

| Master’s degree | 16 (10.1%) |

| Doctorate or professional degree (e.g., PhD, MD, JD, DDS) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Graduate of a Certificate Program | 1 (0.6%) |

| Income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 43 (27.2%) |

| 10,000 – 19,999 | 38 (24.1%) |

| 20,000 – 29,999 | 16 (10.1%) |

| 30,000 – 39,999 | 12 (7.6%) |

| 40,000 – 49,999 | 11 (7%) |

| 50,000 – 59,999 | 14 (8.9%) |

| 60,000 - 69,999 | 5 (3.2%) |

| 70,000 - 79,999 | 8 (5.1%) |

| 80,000 - 89,999 | 4 (2.5%) |

| 90,000-99,999 | 0 |

| More than $100,000 | 6 (3.8%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

Sociopolitical context: state-level

We operationalized sociopolitical context at the state level by characterizing the state of residence of each participant in terms of structural equality and overall sociopolitical context using the ratings provided by the Movement Advancement Project (MAP), which tracks over 50 different LBGTQI+-related laws and policies by state (Movement Advancement Project 2022). These include policies and laws most impactful in the lives of trans people such as state nondiscrimination laws, policies regarding correcting identity documents, criminal justice laws (e.g., hate crimes laws), and healthcare laws and policies. Each state is rated based on the presence/absence of protective, antidiscrimination policies and the presence/absence of harmful policies. Higher scores reflect a more positive sociopolitical context, and lower scores reflect a more negative sociopolitical context. Based on these criteria, each state in this study was rated as follows: Oregon = high (earned 75-100% of possible points); Michigan = fair (earned 25–49.9% of possible points); Nebraska and Tennessee = negative (earned < 0 points). Participants living in NE and TN were thus combined into one group given they received the same rating from the MAP report.

Sources of consistent and decreased support

Participants completed a baseline checklist to assess which relationships participants felt provided support and which relationships had become less affirming since the 2016 election. Relationship options included: no one, partner, strangers, cisgender friends, transgender friends, family members, coworkers, support groups/community organizations, not listed (with a text response box).

Impacts of structural-level sociopolitical events

To assess individual reactions and understand differential group-level impacts of certain structural-level sociopolitical events, participants completed a series of 17 items assessing post-event changes at baseline and in the monthly surveys. Each set of questions focused on specific key events. Impacts of key events in the present analysis include: 1) baseline reflections on the 2016 US presidential election (Donald Trump versus Hillary Clinton), 2) baseline reflections on impacts of the 2018 Trump administration leaked memo which suggested a potential federal-level shift whereby both gender and sex would be re-defined as “a biological, immutable condition determined by genitalia at birth” (Green, Brenner, and Pear 2018), and 3) one of the monthly surveys, in which participants reflected on impacts of the November 2020 US presidential election (Donald Trump versus Joe Biden).

Each questionnaire named the specific event and asked participants to reflect on the impact of this event in their lives using a 7-point “degree of change” scale (1 = extremely decreased, 4 = about the same, 7 = extremely increased). For analyses, participants were then dichotomized into sub-groups reflecting 1) those reporting negative impacts (i.e., those reporting increased negative and decreased positive experiences) and 2) all other participants (i.e., those reporting decreased negative, increased positive, and neutral experiences).

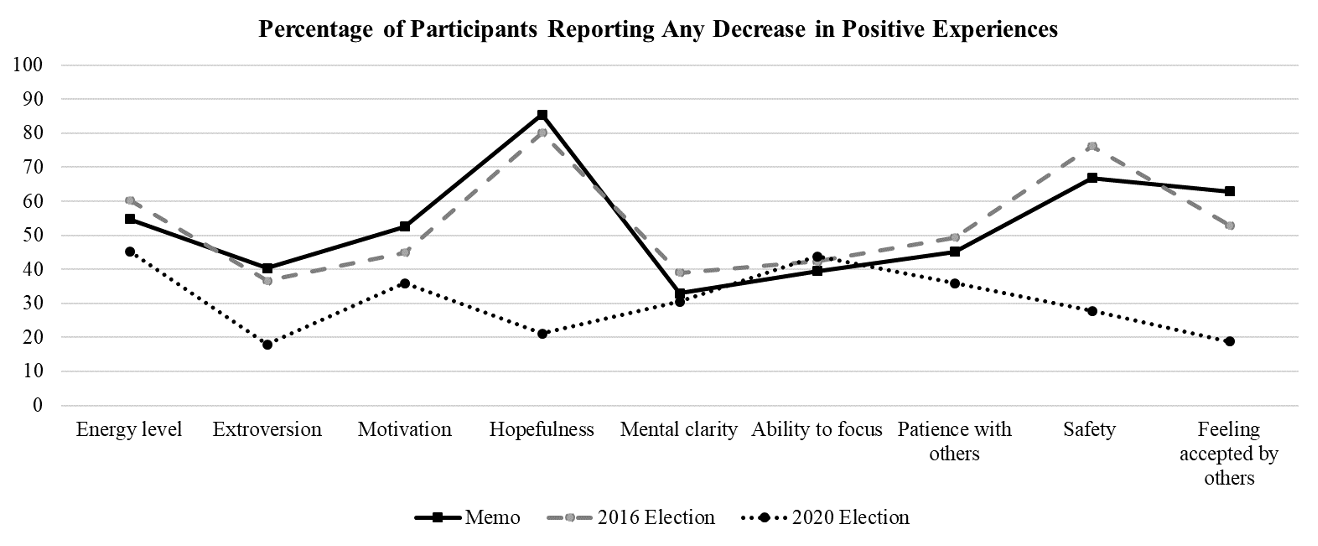

Figure 1. Decreased positive experiences in response to key events

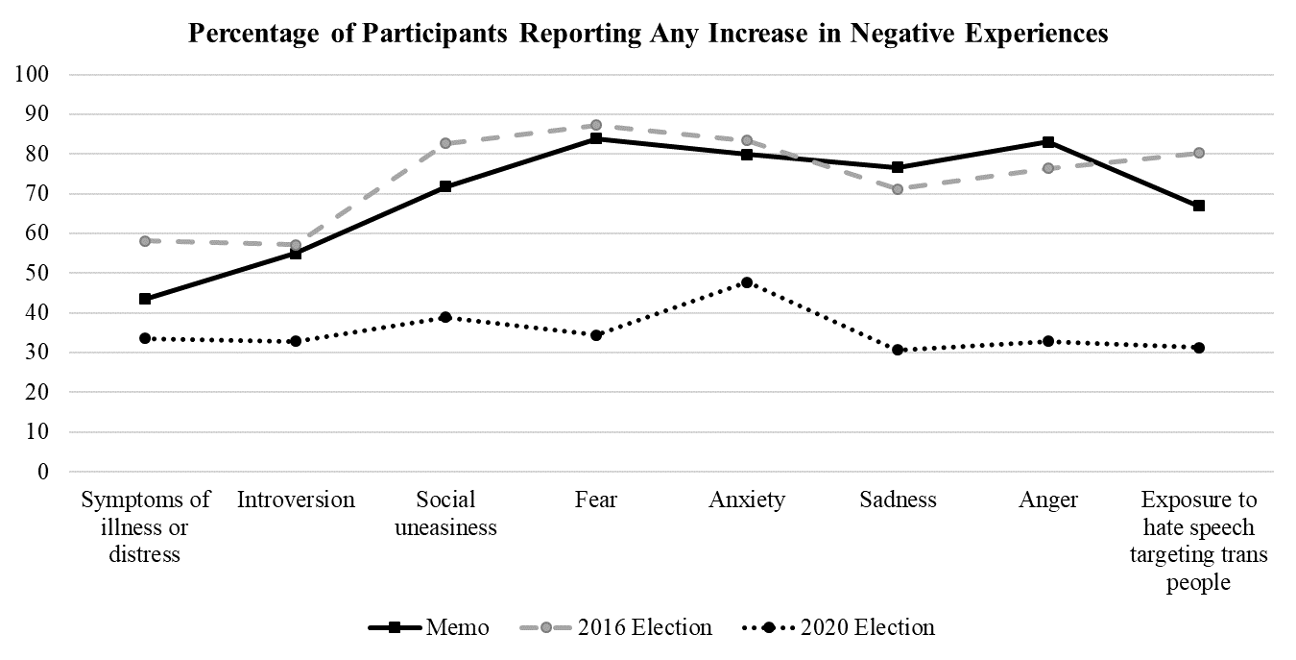

Figure 2. Increased negative experiences in response to key events

Results

Figures 1 and 2 present an overview of the effects of the 2016 presidential election, the 2018 memo leak, and the 2020 presidential election, on participants in this study.

Impacts of the 2016 US presidential election

A substantial portion of our sample reported overall negative impacts of the 2016 election (see Table 2 for a full description). Participants reported decreased positive experiences (ranging from slight to extreme) including hopefulness (80.1%), safety (76.2%), energy level (60.3%), feeling accepted by others (52.9%), patience with others (49.3%), motivation (44.9%), ability to focus (42.3%), mental clarity (39%), and extroversion (36.6%). Participants also reported increased negative experiences (ranging from slight to extreme), including increased fear (87.2%), anxiety (83.4%), social uneasiness (82.7%), exposure to hate speech targeting trans people (80.2%), anger (76.3%), sadness (71.2%), physical symptoms of illness or distress (58.1%), and introversion (57.1%). Most notably, nearly a quarter (23.9%) of participants reported experiencing an extreme increase in exposure to hate speech targeting trans people following the 2016 election.

For simplicity in presentation, we summarize the main findings related to demographic differences in the impacts of the 2016 election rather than each item. Age was unrelated to any of the items. Participants of color (47.9%) were more likely to report decreased feelings of extroversion compared to white participants (31.5%); χ^2^ (1, n = 156) = 3.87, p < .05. Individuals in urban areas (54.7%) were more likely to report decreased motivation compared to people in suburban (33.3%) and rural (38.5%) areas; χ^2^ (2, n = 155) = 6.25, p < .05. Additionally, using the MAP context designation at the state-level, individuals living in areas characterized as negative sociopolitical contexts (68.5%) were more likely to report decreased energy compared to those living in high inclusion contexts (61.4%) or those living in contexts rated as fair (43.6%); χ^2^ (2, n = 156) = 6.61, p < .05. Individuals in negatively rated sociopolitical contexts (56.2%) were also more likely to report decreased motivation compared to those in positive, high inclusion contexts (38.6%) or those in contexts rated as fair (30.8%); χ^2^ (2, n = 156) = 7.59, p < .05.

We found that nonbinary/genderqueer participants (70.8%) and trans masculine participants (66.1%) were more likely to report decreased energy compared to trans feminine (41.7%) participants; χ^2^ (2, n = 155) = 9.99, p < .01. Nonbinary/genderqueer participants (58.3%) were also more likely to report decreased motivation compared to trans masculine (44.1%) and trans feminine (31.3%) participants; χ^2^ (2, n = 155) = 7.14, p < .05, and to report having decreased ability to focus (54.2%) compared to trans masculine (44.1%) and trans feminine participants (27.1%); χ^2^ (2, n = 155) = 7.41, p < .05. In addition, trans masculine participants (59.3%) were more likely to report decreased patience for others compared to nonbinary/genderqueer (52.1%) and trans feminine participants (33.3%); χ^2^ (2, n = 155) = 7.41, p < .05.

In terms of sources of support since the 2016 election, 1.9% (n = 3) of participants reported support from no one, 17.1% (n = 27) from strangers, 39.9% (n = 63) from coworkers, 46.8% (n = 74) from family members, 55.7% (n = 88) from support groups and community organizations, 63.3% (n = 100) from a partner, 70.9% (n = 112) from cisgender friends, and 82.9% (n = 131) from trans friends. Some participants (n = 10; 6.3%) indicated that they received support from other options that were not listed. This support came from people like therapists, teachers or mentors, and other forms of community, like drag culture and online organizations. In contrast, when asked who had become less affirming since the 2016 election, participants endorsed the following: 1.3% (n = 2) trans friends, 2.5% (n = 4) partner, 6.3% (n = 10) support groups and community organizations, 15.8% (n = 25) no one, 21.5% (n = 34) cisgender friends, 25.9% (n = 41) coworkers, 59.5% (n = 94) strangers, and 43% (n = 68) family members. An additional 5.7% (n = 9) of participants indicated that other people who were not listed had become less affirming since the 2016 election. Written responses included celebrities, churches, professors and students, housemates, and the government.

Table 2. Post-2016 Election Changes

| Type of Change: | Extremely Decreased | Moderately Decreased | Slightly Decreased | About the Same | Slightly Increased | Moderately Increased | Extremely Increased |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy level | 26 (16.7%) | 36 (23.1%) | 32 (20.5%) | 46 (29.5%) | 9 (5.8%) | 5 (3.2%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Physical symptoms of illness or distress | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | 4 (2.6%) | 59 (38.1%) | 42 (27.1%) | 30 (19.4%) | 18 (11.6%) |

| Introversion/desire to be alone | 2 (1.3%) | 6 (3.8%) | 9 (5.8%) | 50 (32.1%) | 36 (23.1%) | 36 (23.1%) | 17 (10.9%) |

| Extroversion/desire to be with others | 11 (7.1%) | 13 (8.3%) | 33 (21.2%) | 49 (31.4%) | 23 (14.7%) | 16 (10.3%) | 11 (7.1%) |

| Motivation | 7 (4.5%) | 25 (16%) | 38 (24.4%) | 42 (26.9%) | 24 (15.4%) | 14 (9%) | 6 (3.8%) |

| Hopefulness | 28 (17.9%) | 48 (30.8%) | 49 (31.4%) | 17 (10.9%) | 6 (3.8%) | 7 (4.5%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Mental clarity | 6 (3.8%) | 27 (17.3%) | 28 (17.9%) | 71 (45.5%) | 14 (9%) | 8 (5.1%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Ability to focus | 9 (5.8%) | 27 (17.3%) | 30 (19.2%) | 73 (46.8%) | 11 (7.1%) | 6 (3.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Social uneasiness | 3 (1.9%) | 7 (4.5%) | 4 (2.6%) | 13 (8.3%) | 54 (34.6%) | 43 (27.6%) | 32 (20.5%) |

| Patience with others | 13 (8.3%) | 23 (14.7%) | 41 (26.3%) | 60 (38.5%) | 12 (7.7%) | 5 (3.2%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Fear | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (1.3%) | 17 (10.9%) | 61 (39.1%) | 55 (35.3%) | 20 (12.8%) |

| Anxiety | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (1.3%) | 3 (1.9%) | 20 (12.8%) | 46 (29.5%) | 53 (34%) | 31 (19.9%) |

| Sadness | 1 (0.6%) | 5 (3.2%) | 3 (1.9%) | 36 (23.1%) | 55 (35.3%) | 39 (25%) | 17 (10.9%) |

| Anger | 2 (1.3%) | 1 (0.6%) | 5 (3.2%) | 29 (18.6%) | 32 (20.5%) | 51 (32.7%) | 36 (23.1%) |

| Safety | 18 (11.5%) | 52 (33.3%) | 49 (31.4%) | 28 (17.9%) | 7 (4.5%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Feeling accepted by others | 13 (8.4%) | 29 (18.7%) | 40 (25.8%) | 52 (33.5%) | 15 (9.7%) | 3 (1.9%) | 3 (1.9%) |

| Exposure to hate speech targeting trans people | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | 2 (1.3%) | 26 (16.5%) | 39 (24.7%) | 49 (31.6%) | 37 (23.9%) |

Note: Percentages are based on the participants who answered these items and participants with missing data were excluded.

Impacts of the 2018 federal memo leak

Table 3 provides an overview of the effects of the 2018 memo leak (described above). We found that 32 participants (20.3%) did not know about the memo leak, and 2 additional participants did not respond to these items. These participants were excluded from all analyses related to the memo leak. Table 3 provides an overview of the effects of the memo leak. In the 2 weeks following this event, participants reported decreases (ranging from slight to extreme) in: hopefulness (85.5%), safety (66.9%), feeling accepted by others (62.9%), energy levels (54.8%), motivation (52.5%), patience with others (45.2%), extroversion (40.4%), ability to focus (39.5%), and mental clarity (33%). Participants also reported increases (ranging from slight to extreme) in the following: fear (83.9%), anger (83%), anxiety (79.9%), sadness (76.6%), social uneasiness (71.8%), exposure to hate speech targeting trans people (66.9%), introversion (54.9%), and physical symptoms of illness or distress (43.5%).

Participants experienced many of the negative consequences of the memo leak regardless of the sociopolitical context of the state they resided in or other aspects of their identity. Age was correlated with three of the items; older participants were more likely to report increased physical symptoms of illness or distress (r = .21, p < .05), decreased extroversion (r = .19, p < .05), and decreased safety (r = .17, p < .05). Participants of color (57.9%) were more likely to report decreased feelings of extroversion compared to white participants (32.6%); χ^2^ (1, n = 124) = 7.03, p < .01. Individuals in suburban areas (85.7%) were more likely to report increases in their social uneasiness compared to people in urban (65.1%) and rural (63.2%) areas; χ^2^ (2, n = 124) = 6.12, p < .05. There were no significant associations between the effects of the memo leak and context via the MAP ratings or gender.

Table 3. Post-2018 Memo Changes

| Type of Change: | Extremely Decreased | Moderately Decreased | Slightly Decreased | About the Same | Slightly Increased | Moderately Increased | Extremely Increased |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy level | 17 (13.7%) | 17 (13.7%) | 34 (27.4%) | 52 (41.9%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Physical symptoms of illness or distress | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (4%) | 65 (52.4%) | 31 (25%) | 16 (12.9%) | 7 (5.6%) |

| Introversion/desire to be alone | 0 (0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 5 (4%) | 47 (37.9%) | 28 (22.6%) | 26 (21%) | 14 (11.3%) |

| Extroversion/desire to be with others | 13 (10.5%) | 13 (10.5%) | 24 (19.4%) | 45 (36.3%) | 14 (11.3%) | 8 (6.5%) | 7 (5.6%) |

| Motivation | 9 (7.3%) | 15 (12.1%) | 41 (33.1%) | 40 (32.3%) | 11 (8.9%) | 5 (4%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Hopefulness | 30 (24.2%) | 39 (31.5%) | 37 (29.8%) | 14 (11.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mental clarity | 6 (4.8%) | 18 (14.5%) | 17 (13.7%) | 77 (62.1%) | 5 (4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ability to focus | 7 (5.6%) | 13 (10.5%) | 29 (23.4%) | 71 (57.3%) | 3 (2.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Social uneasiness | 3 (2.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 9 (7.3%) | 22 (17.7%) | 33 (26.6%) | 32 (25.8%) | 24 (19.4%) |

| Patience with others | 8 (6.5%) | 17 (13.7%) | 31 (25%) | 61 (49.2%) | 4 (3.2%) | 1 (0.8%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Fear | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 20 (16.1%) | 38 (30.6%) | 40 (32.3%) | 26 (21%) |

| Anxiety | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (20.2%) | 31 (25%) | 39 (31.5%) | 29 (23.4%) |

| Sadness | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 28 (22.6%) | 38 (30.6%) | 33 (26.6%) | 24 (19.4%) |

| Anger | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 20 (16.1%) | 37 (29.8%) | 33 (26.6%) | 33 (26.6%) |

| Safety | 17 (13.7%) | 37 (29.8%) | 29 (23.4%) | 37 (29.8%) | 3 (2.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Feeling accepted by others | 22 (17.7%) | 32 (25.8%) | 24 (19.4%) | 41 (33.1%) | 3 (2.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Exposure to hate speech targeting trans people | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 40 (32.3%) | 33 (26.6%) | 18 (14.5%) | 32 (25.8%) |

Note: Percentages are based on the participants who answered these items and participants with missing data or those who were unaware of the memo were excluded.

Impacts of the 2020 US presidential election

Table 4 provides an overview of the effects of the 2020 election. Participants reported decreases (ranging from slight to extreme) in the following: energy level (45.3%), ability to focus (43.8%), motivation (35.9%), patience with others (35.9%), mental clarity (30.5%), safety (27.8%), hopefulness (21.1%), feeling accepted by others (18.8%), and extroversion (18.0%). Participants also reported increases (ranging from slight to extreme) in the following: anxiety (47.7%), social uneasiness (38.9%), fear (34.4%), physical symptoms of illness or distress (33.6%), introversion (32.8%), anger (32.8%), exposure to hate speech targeting trans people (31.3%), and sadness (30.7%).

Older participants reported more sadness after the 2020 election (r = .23, p < .01). Participants of color (51.4%) were more likely to report decreased motivation after the 2020 election compared to white participants (29.7%); χ^2^ (1, n = 128) = 5.37, p < .05, as well as decreased hopefulness (32.4%) compared to white participants (16.5%); χ^2^ (1, n = 128) = 4.02, p < .05. Participants of color (45.9%) were also more likely to report decreased mental clarity compared to white participants (24.2%); χ^2^ (1, n = 128) = 5.89, p < .05. Participants of color (51.4%) were more likely to report increased fear compared to white participants (27.5%); χ^2^ (1, n = 128) = 6.65, p < .05, and increased anxiety (62.2%) compared to white participants (41.8%); χ^2^ (1, n = 128) = 4.39, p < .05. Finally, participants of color (42.9%) were more likely to report decreased safety compared to white participants (22.0%); χ^2^ (1, n = 128) = 5.49, p < .05.

In relation to urban/rural residence, individuals in urban areas (50.0%) were more likely to report increased fear compared to individuals in suburban (25.0%) or rural areas (14.3%); χ^2^ (2, n = 127) = 11.86, p < .01. Urban participants (58.6%) were also more likely to report increased anxiety compared to rural participants (28.6%); χ^2^ (2, n = 127) = 6.14, p < .05. There was not a significant association between sociopolitical context based on state-based MAP designation and any reactions to the 2020 election. Nonbinary/genderqueer participants (50.0%) were more likely to report decreased motivation compared to trans masculine participants (23.1%); χ^2^ (2, n = 127) = 6.97, p < .05, as well as decreased ability to focus (61.1%) compared to trans masculine participants (30.8%); χ^2^ (2, n = 127) = 8.04, p < .05. Nonbinary/genderqueer participants (44.4%) were also more likely to report increased sadness compared to trans masculine participants (19.2%); χ^2^ (2, n = 126) = 6.60, p < .05. Trans feminine participants (41.0%) and trans masculine participants (34.6%) were more likely than nonbinary/genderqueer participants (13.9%) to report increased exposure to hate speech; χ^2^ (2, n = 127) = 7.11, p < .05.

Table 4. Post-2020 Election Changes

| Type of Change: | Extremely Decreased | Moderately Decreased | Slightly Decreased | About the Same | Slightly Increased | Moderately Increased | Extremely Increased |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy level | 13 (10.2%) | 25 (19.5%) | 20 (15.6%) | 39 (30.5%) | 18 (14.1%) | 13 (10.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Physical symptoms of illness or distress | 5 (3.9%) | 5 (3.9%) | 13 (10.2%) | 62 (48.4%) | 24 (18.8%) | 16 (12.5%) | 3 (2.3%) |

| Introversion/desire to be alone | 3 (2.3%) | 6 (4.7%) | 21 (16.4%) | 56 (43.8%) | 25 (19.5%) | 9 (7.0%) | 8 (6.3%) |

| Extroversion/desire to be with others | 7 (5.5%) | 3 (2.3%) | 13 (10.2%) | 50 (39.1%) | 35 (27.3%) | 15 (11.7%) | 5 (3.9%) |

| Motivation | 11 (8.6%) | 14 (10.9%) | 21 (16.4%) | 36 (28.1%) | 33 (25.8%) | 12 (9.4%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Hopefulness | 6 (4.7%) | 11 (8.6%) | 10 (7.8%) | 28 (21.9%) | 36 (28.1%) | 24 (18.8%) | 13 (10.2%) |

| Mental clarity | 8 (6.3%) | 7 (5.5%) | 24 (18.8%) | 64 (50.0%) | 18 (14.1%) | 7 (5.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Ability to focus | 11 (8.6%) | 13 (10.2%) | 32 (25.0%) | 51 (39.8%) | 10 (7.8%) | 11 (8.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Social uneasiness | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (3.2%) | 14 (11.1%) | 58 (46.0%) | 23 (18.3%) | 17 (13.5%) | 9 (7.1%) |

| Patience with others | 6 (4.7%) | 8 (6.3%) | 32 (25.0%) | 61 (47.7%) | 14 (10.9%) | 6 (4.7%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Fear | 2 (1.6%) | 8 (6.3%) | 25 (19.5%) | 49 (38.3%) | 28 (21.9%) | 11 (8.6%) | 5 (3.9%) |

| Anxiety | 3 (2.3%) | 9 (7.0%) | 14 (10.9%) | 41 (32.0%) | 31 (24.2%) | 16 (12.5%) | 14 (10.9%) |

| Sadness | 3 (2.4%) | 9 (7.1%) | 13 (10.2%) | 63 (49.6%) | 25 (19.7%) | 7 (5.5%) | 7 (5.5%) |

| Anger | 2 (1.6%) | 6 (4.7%) | 14 (10.9%) | 64 (50.0%) | 29 (22.7%) | 7 (5.5%) | 6 (4.7%) |

| Safety | 4 (3.2%) | 10 (7.9%) | 21 (16.7%) | 63 (50.0%) | 20 (15.9%) | 5 (4.0%) | 3 (2.4%) |

| Feeling accepted by others | 2 (1.6%) | 5 (3.9%) | 17 (13.3%) | 79 (61.7%) | 15 (11.7%) | 9 (7.0%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Exposure to hate speech targeting trans people | 2 (1.6%) | 3 (2.3%) | 8 (6.3%) | 75 (58.6%) | 20 (15.6%) | 15 (11.7%) | 5 (3.9%) |

Note: Percentages are based on the participants who answered these items and participants with missing data were excluded.

Discussion

This study examined how trans people living in four different states in the US responded to key societal events, each highlighting aspects of structural stigma. These events included the 2016 US presidential election of Donald Trump, the 2020 US presidential election of Joe Biden, and the 2018 memo leak from the Trump administration that suggested narrowing the definition of gender and sex, which would exclude and negatively impact trans people. Drawing on theories of stigma as a social determinant of health (Brewis and Wutich 2020; Goffman 1963; Link and Phelan 2001; 2014), as well as socioecological models to interpret the impacts of these events, we can elaborate further the ways that multiple levels of oppression negatively affect the lives of people facing marginalization and inequality (Bronfenbrenner 1977; Hughto, Reisner, and Pachankis 2015; Puckett et al. 2022a). Overall, our findings expose the powerful impact structural stigma can have on trans people's lives and highlight how certain key events can threaten trans quality or equality of life.

Our findings provide a striking example of the impacts of structural stigma on trans people as reflected in the high percentage of participants who reported negative impacts particularly from the 2016 election and 2018 memo leak. Most alarming is the fact that nearly a quarter of participants in this study experienced an extreme increase in exposure to hate speech targeting trans people following the 2016 election of President Trump. These findings are aligned with others documenting the harmful effects of the 2016 election on LBGTQI+ people more broadly, pointing to a period of increased risk for structural stigma, including discriminatory legislation, stigmatizing political campaigns, and increased anti-LBGTQI+ policies (Gonzalez, Ramirez, and Galupo 2018; Veldhuis et al. 2018).

These reports of increased verbal attacks through hate speech since the 2016 election also align with reports of a massive increase (226%) in hate crimes, particularly those targeting minority populations in counties where Trump rallies were held during the 2016 campaign (Feinberg, Branton, and Martinez-Ebers 2019; Warren-Gordon and Rhineberger 2021). Our findings are in line with a recent study among sexual minority women and trans feminine people which also found heightened threats to safety, civil rights, psychological, and emotional well-being due to increased structural stigma after the 2016 presidential election (Veldhuis et al. 2018). Additional support for our findings is seen in another recent study which revealed that following the 2016 election, anti-trans political rhetoric and stigmatization were found to have effects on the mental and physical health of trans people because of the increased threat of physical violence and compounding effects of marginalization stress (Price, Puckett, and Mocarski 2021). Together, with these findings, our results demonstrate how sociopolitical events reflect and also impact the contexts in which they occur, thereby shaping experiences of minority stressors.

In addition to increased experiences of direct physical and verbal attacks and violence, the sociocultural and political climate can take a direct toll on mental and physical health, as exhibited by our results. For example, in terms of mental health effects, in their study of minority stress experiences in LBGTQI+ individuals before and after the 2016 election, Gonzalez and colleagues found that participants experienced significantly higher levels of minority stress pertaining to rumination, daily harassment, and discrimination, as well as increased levels of depression and anxiety (2018). Similarly, sexual minority women and gender minority individuals felt they were at increased risk of experiencing discrimination after the 2016 election (Riggle et al. 2018; Veldhuis et al. 2018). A majority of participants, all of whom identified as trans, reported increased negative experiences following the 2016 election, including increased fear and anxiety, with nearly a quarter of participants reporting an extreme increase in exposure to hate speech towards trans people. On top of this, the nonbinary/genderqueer participants were more likely to report negative impacts on their energy, motivation, and focus, compared to trans masculine and trans feminine participants, illuminating the discrepant experiences between trans masculine and trans feminine individuals and those whose identities fall outside of the gender binary (Matsuno et al. 2022). Nonbinary/genderqueer individuals experience elevated discrimination and marginalization amplified by the systemic enforcement of gender binarism (e.g., political oppression, rejection, interpersonal invalidation) resulting in unique experiences of minority stress (Matsuno et al. 2022; Puckett et al. 2021).

These findings linking sociopolitical context to mental health and well-being have further relevance as impacts of marginalization, minority stress, and stigma can also negatively affect physical health and chronic disease risk (Hatzenbuehler 2009; Hatzenbuehler and McLaughlin 2014). A recent study of embodied minority stress among trans masculine people found lower stress-induced physical “wear and tear” as measured through allostatic load among those who perceived themselves as living in more politically progressive areas compared to those in more politically conservative areas (DuBois and Juster 2022). Similarly, recent research shows that trans people who are aware of anti-trans legislation efforts in their states experience a stronger impact of discrimination on belonging and hopelessness compared to trans individuals who are not aware of such efforts in their state (Tebbe et al. 2022). This implies that the effects of minority stressors may vary depending on the broader sociopolitical context trans people are living in. Our findings show similarly negative effects in these contexts when it came to the 2016 election of Donald Trump; individuals living in negatively rated sociopolitical contexts/states were more likely to report negative health effects (i.e., decreased energy and motivation), compared to those living in areas rated as positive and high-inclusion contexts. This further underscores the importance of considering the impact of sociopolitical events and the contexts in which they take place, particularly when examining social determinants of health (Tebbe et al. 2022).

Our findings also suggest that major sociopolitical events need to be recognized as complex and their impacts need to be assessed with recognition of other contextual factors. For instance, the 2020 election of President Biden, which may have brought relief to many trans people given the negative impact of the Trump administration on trans people’s lives, was also accompanied by significant political backlash in the form of capitol riots, protests, and armed militias threatening marginalized communities, to name a few. In addition to President Biden’s election in 2020 and the surrounding political climate and backlash, the COVID-19 pandemic was on-going, exacerbating existing inequalities, marginalization, and social isolation many trans people experience (Gibb et al. 2020). As such, we acknowledge that it is difficult to describe the 2020 election in strict binary (positive/negative) ways as these may mask the complicated nature of such events within this broader political climate, and that participant responses would be inseparable from that broader context. Nonetheless, in our study, participants recalled their experience as trans people during this time with about 30% of participants reporting an increase in exposure to hate speech after the 2020 election of President Biden. We interpret this increase as another example of the political backlash that followed the election with negative impacts for trans people. Along these lines, others have noted that generally there can be sociopolitical turmoil during periods of transition such as these, so they are never uniformly “positive” (Russell et al. 2011).

In terms of the individual responses to these events and their impacts, we identified important differences in the types of experiences that are impacted by different events. Broadly speaking, “negative” sociopolitical events harmed trans people in this study in two ways - by decreasing positive experiences and increasing negative experiences. The 2016 presidential election through which Trump became President and the 2018 memo leak, which threatened a federal re-definition of “sex” as biological and unchangeable from assigned birth sex, were especially impactful through decreasing participants’ sense of hopefulness, safety, and feelings of being accepted by others. Moreover, these events increased participants' negative experiences and emotions. These findings are consistent with other studies of the 2016 or 2020 elections - in particular, Price et al., (2021) who found that political rhetoric and stigmatization of trans people impacts mental and physical health due to their elevated risk of physical violence, discrimination, and marginalization stress.

While all participants were familiar with the 2 presidential elections, 1 out of 5 of our participants were unfamiliar with the content of the 2018 memo leak. This may reflect media and news avoidance as additional ways trans people may respond and cope with these stressors and challenges (Gorman et al. 2020; Puckett et al. 2020; Rood et al. 2017; 2016). Trans people engage in many forms of coping with stigma and minority stress. For example, when trans people were asked about their experiences of social rejection and how they coped with perceived hostility, avoidance, and escape (e.g., leaving the situation when possible) were common coping strategies (Rood et al. 2016). In a more recent study, coping strategies involving detachment or withdrawing from a situation were also associated with heightened depression and anxiety (Puckett et al. 2020).

Nonetheless, avoidant coping strategies implemented by trans people to protect themselves from discrimination may reflect an adaptive technique unique to marginalized groups. Given the cisgender-focused coping literature, avoidance coping is often interpreted as a negative coping mechanism (Gorman et al. 2020). Rood et al. (2017) showed how negative social messages regarding trans people originating in media like television shows and movies led to reports of emotional distress (i.e., angry/frustrated, sad/hurt, fearful/anxious, dehumanized/devalued) among trans participants. Kteily and Bruneau (2016) expanded on the impacts of dehumanization on minority populations, suggesting that advantaged groups use this tactic to perpetuate the marginalization of other groups for self-fulfilling purposes. As such, the negative effects of bias portrayed in the media may lead trans people to avoid the news, which could help to explain why a quarter of our participants were unfamiliar with the memo leak. Furthermore, it is possible that this may be a helpful coping strategy when managing such pervasive anti-trans rhetoric.

When comparing different demographic groups within our study, participants of color reported decreased feelings of extroversion/desire to be with others in response to both the 2016 election and 2018 memo leak, along with decreased motivation, hopefulness, mental clarity, and safety, and increased fear and anxiety after the 2020 election. This, again, may reflect experiences of backlash and emphasize the heightened racist violence in the US; the 2020 election occurred at a time of greater societal engagement with the Black Lives Matter movement and on-going protests against police brutality and police murder of Black people (McManus et al. 2019). Several recent studies have discussed similar impacts of sociopolitical marginalization and structural stigma on sexual and gender minority people of color (Gorman et al. 2020; James et al. 2016; Rood et al. 2016). A recent systematic review focuses specifically on the health and well-being of trans people of color in the US, pointing to the varied experiences and different forces that may shape health and health disparities among trans communities of color (Farvid et al. 2021). Moreover, in a study by Rood and colleagues (2017), trans participants of color also expressed feeling better prepared to face and cope with anti-trans discrimination and stigma because of chronic experiences of racism and race-related discrimination. The broader context of the 2020 election also included the COVID-19 pandemic, the police murder of George Floyd and other Black people, the Black Lives Matter movement and associated protests, all occurring alongside local level events (e.g., wildfires in Oregon). It is thus clear that multiple structural drivers of systemic, racial oppression occurred during this time, raising concerns like immigration status and economic precarity, for instance, which might have differential effects on participants of color in our study (Stone et al. 2020). The intersection of events and experiences undoubtedly influenced participant reflections on the events themselves. The broader political climate in which these events occurred also likely brought existing health and economic inequalities, systemic oppression, and racism to the forefront of participants’ minds. In this study, we asked participants to reflect on their responses to specific events, not to try to disentangle or explain their responses in relation to other on-going events or experiences. Participant reflections thus represent how they recall their responses and attribute those responses to certain events included in our survey – within the broader context in which they were occurring.

Reflecting similar findings to Ralston et al. (2022), we also see interesting variation in responses based on rural versus urban residency. The most striking differences were seen in relation to the 2020 election where individuals residing in urban areas were more likely to report increased fear and anxiety compared to those living in rural or suburban areas. It is possible that trans people in rural areas have come to expect anti-trans sentiment in their areas (e.g., trans youth in rural areas experience greater bullying than trans youth in urban areas (Eisenberg et al. 2019). Thus, any backlash occurring after the election may have been expected by trans people living in rural compared to more urban areas. It also may be that more urban areas provide a sense of anonymity to those perpetuating anti-trans stigma and that this could heighten trans people’s vigilance about others, whereas in rural communities there is less anonymity and communities are more close-knit.

Support and supportive resources are vital to combat the impacts of stigma and inequality endured by trans people. However, research also shows that the type of support that trans people have access to is important to health and resilience (Puckett et al. 2019). Considering the increased risk of exposure to hate speech and violence, and the direct effects on mental and physical health following these events, we examined support systems after the 2016 election. Most participants reported accessing support from friends (especially those friends who also identify as trans) and support groups/community organizations. In contrast, less than half (46.8%) reported accessing support from family. These findings are consistent with those of Gonzalez et al. (2018) who found stronger connections of support reported within the LBGTQI+ community following the 2016 election, despite increased levels of minority stress, anxiety, depression, and experiences of discrimination and harassment. Another study however, found that anti-trans political rhetoric and policies targeting the LGBTQI+ community as a whole, can lead to increased feelings of isolation for some trans people, even within their own communities (Price, Puckett, and Mocarski 2021). Furthermore, though perhaps not surprisingly, given the reports of increased hate speech, participants reported negative changes in their relationships. Since the 2016 election, most participants said they felt that strangers had become less affirming, nearly half said family members had become less affirming, and a quarter said coworkers had become less affirming. Trans people understandably experience elevated stress levels in unsafe or un-affirming social environments, underscoring the significance of validating social relationships and support systems for health and well-being (Gorman et al. 2020). Over the course of this study, extremist political discourse and a heavily politicized pandemic may also have shifted support systems for our participants, further exacerbating experiences of marginalization and social isolation. Given the importance of familial support, and support in general, in relation to mental health and resilience, these findings are concerning and again emphasize how individual experiences are embedded within the broader sociopolitical climate.

Overall, these findings thus highlight the importance of collecting contextual data concerning structural changes and stigma, as there is not a single, homogenous experience for trans people in the US or elsewhere. The impacts of sociopolitical events vary by location, individual identities, and other factors including the cultural contexts within which they occur. Moreover, they sadly reflect the fact that some communities may continue to endure high rates of hardship even in the wake of relatively “positive” events. Again, this reflects the complexity of these events and the contexts in which they occur and suggest individuals may be managing political reactions such as increased bias, occurring in tandem with structural level change.

Strengths, limitations, and future research

As a contribution to the limited literature on trans people’s experiences of structural stigma and contemporary political events, the current study offers several strengths. This study is one of the first to draw on data collected across multiple cross-sections of time to examine the impact of a series of sociopolitical events on trans people. Combined with a socioecological and gender minority stress framework, our results provide insight into the importance of structural level inequalities, stigma, and their impacts on trans people (Puckett et al. 2022a). Future research should continue building on socioecological frameworks to expand minority stress theory and literature to better reflect the contextual factors that shape trans people’s lived experiences and health. This study also expands on previous literature about the negative impacts of anti-LBGTQI+ policies and other sociopolitical events more broadly on LBGTQI+ people at the individual, community, and sociocultural levels (Frost and Fingerhut 2016; Hatzenbuehler 2017; Hatzenbuehler et al. 2011; Hughto et al. 2021; Russell et al. 2011).

Several limitations should also be considered when assessing the results of this study. First, all participants in this study identified as trans, a population currently underrepresented in the literature, but this sample is not representative of all trans people. Future studies could incorporate a more diverse range of gender and sexual identities to examine how intersecting identities (e.g., gender, ethnicity, sexual identity) may impact an individual's experience, exposure, and response to sociopolitical events. Second, our sample is diverse in terms of state of residence as participants were enrolled from four different states reflecting variable legislative protections and forms of support available. However, the study was less diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, and certain socioeconomic characteristics. For instance, our sample was mostly white (30.4% participants of color), and trans people of color endure disproportionate discrimination compared to white counterparts (James et al. 2016; Gorman et al. 2020; Rood et al. 2016; 2017; Veldhuis et al. 2018). The COVID-19 pandemic and the heightened visibility of social movements, including the Black Lives Matter movement, in response to the police murder of George Floyd and other Black people, accentuated the health, economic, and systemic disparities particularly faced by people of color. As such, our findings cannot be generalized and likely underestimate the impacts of these sociopolitical events on trans people of color. Finally, though participants in our study are relatively well-educated/accessing higher education, with more than half completing at least an associate degree, most of the participants were low-income (less than $30,000), likely reflecting the stigma and socioeconomic disparities prevalent for trans people (Kenagy 2005; Xavier, Honnold, and Bradford 2007). Future research could elaborate on understandings of these socioeconomic inequalities and their intersection with experiences of stigma.

Conclusions

This research aimed to illuminate the impacts of sociopolitical contexts and key events on trans people’s health, well-being, and resilience, and contribute to our understanding of how multiple levels of oppression negatively affect the lives of trans people. Overall, our findings expose the powerful impact structural inequality and stigma has on trans people's lives. Through our assessment of the impact of three key events, the 2018 memo leak and the 2016 and 2020 US presidential elections, we found “negative” events (the memo leak and 2016 election of Trump) had negative impacts on participants by increasing several negative experiences, while also decreasing participants’ positive experiences and emotions. In particular, the increase in exposure to hate speech reported by a majority of study participants following the 2016 election highlights the critical link between sociopolitical contexts, structural stigma, and the risk to trans people in daily life. These findings point to the need to move beyond individual and interpersonal levels of analyses to include structural-level analyses within sociopolitical contexts. Although it may be clear how policies directly denying services or human rights to trans people can harm health and well-being, the impacts of negative sociopolitical contexts on health can often be underestimated. Our findings support recognizing that a stigmatizing political climate can and should be considered a social determinant of health. These findings thus have implications for policy and practice; certainly, reducing structural stigma is necessary as a long-term goal. But so is increasing the provision of support and community connection where possible in the more immediate future to ameliorate harmful effects of structural stigma and isolation which may take much longer to address.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the community board associated with Trans Collaborations in Nebraska for their thoughtful feedback. We also deeply appreciate the time of all the participants who contributed to this study. This study also would not have been possible without the many dedicated research team members across all sites. We wish to thank Geeta Eick, Bex Macfife, Holly Moulton, Lindsey Foltz, Oliver Hoover, Jaden Haun, Beyla Geoffrey, Alex Jagielski, Julia Rohrabaugh, Lauren King Watt, Felix Hart, Judith Moman, Dee Jolly, Rin Nguyen, Maryam Razzaq, Terra Dunn, Bella Andrus, Kalei Glozier, Rowan Giffel, Felix Brown, Taylor Anderson, Devon Kimball, Callie Harris, Megan Wertz, Heather Barnes, Lex Pulice-Farrow, and Drs. Kirsten Gonzalez, Jennifer Jabson-Tree, and Cindi SturtzStreetharan for their involvement in this work.

References

Arayasirikul, Sean, and Erin C. Wilson. 2019. “Spilling the T on Trans-Misogyny and Microaggressions: An Intersectional Oppression and Social Process Among Trans Women.” Journal of Homosexuality 66 (10): 1415–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1542203.

Bockting, Walter O, Michael H Miner, Rebecca E Swinburne Romine, Autumn Hamilton, and Eli Coleman. 2013. “Stigma, Mental Health, and Resilience in an Online Sample of the US Transgender Population.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (5): 943–51. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2013.301241.

Breslow, Aaron S, Melanie E Brewster, Brandon L Velez, Stephanie Wong, Elizabeth Geiger, and Blake Soderstrom. 2015. “Resilience and Collective Action: Exploring Buffers Against Minority Stress for Transgender Individuals.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2 (3): 253–65. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000117.

Brewis, Alexandra, and Amber Wutich. 2020. “Stigma: A Biocultural Proposal for Integrating Evolutionary and Political‐economic Approaches.” American Journal of Human Biology 32 (4): e23290. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23290.

Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1977. “Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development.” American Psychologist 32 (7): 513–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.32.7.513.

Brooks, Virginia R. 1981. Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Collins, Patricia Hill. 2015. “Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas.” Annual Review of Sociology 41 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112142.

Conron, Kerith J., Kathryn K. O’Neill, Luis A. Vasquez, and Christy Mallory. 2022. Prohibiting Gender-Affirming Medical Care for Youth. Los Angeles: Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/bans-trans-youth-health-care/.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989 (1). http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43(6): 1241–99.

DuBois, L. Zachary, James K. Gibb, Robert Paul Juster, and Sally I. Powers. 2021. “Biocultural Approaches to Transgender and Gender Diverse Experience and Health: Integrating Biomarkers and Advancing Gender/Sex Research.” American Journal of Human Biology 33 (1): e23555. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23555.

DuBois, L. Zachary, and Robert-Paul Juster. 2022. “Lived Experience and Allostatic Load Among Transmasculine People Living in the United States.” Psychoneuroendocrinology 143: 105849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2022.105849.

Eisenberg, Marla E., Amy L. Gower, Barbara J. McMorris, G. Nicole Rider, and Eli Coleman. 2019. “Emotional Distress, Bullying Victimization, and Protective Factors Among Transgender and Gender Diverse Adolescents in City, Suburban, Town, and Rural Locations.” The Journal of Rural Health 35 (2): 270–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12311.

Farvid, Panteá, Thomas A. Vance, Samantha L. Klein, Yekaterina Nikiforova, Lisa R. Rubin, and Felix G. Lopez. 2021. “The Health and Wellbeing of Transgender and Gender Non‐conforming People of Colour in the United States: A Systematic Literature Search and Review.” Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 31 (6): 703–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2555.

Feinberg, Ayal, Regina Branton, and Valerie Martinez-Ebers. 2019. “Counties That Hosted a 2016 Trump Rally Saw a 226 Percent Increase in Hate Crimes.” The Washington Post, March 22, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2019/03/22/trumps-rhetoric-does-inspire-more-hate-crimes/.

Frost, David M., and Adam W. Fingerhut. 2016. “Daily Exposure to Negative Campaign Messages Decreases Same-Sex Couples’ Psychological and Relational Well-Being.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 19 (4): 477–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430216642028.

Gibb, James K., L. Zachary DuBois, Sarah Williams, Luseadra McKerracher, Robert Paul Juster, and Jessica Fields. 2020. “Sexual and Gender Minority Health Vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 Health Crisis.” American Journal of Human Biology 32 (5): e23499. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23499.

Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Prentice-Hall.

Gonzalez, Kirsten A., Johanna L. Ramirez, and M. Paz Galupo. 2018. “Increase in GLBTQ Minority Stress Following the 2016 US Presidential Election.” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 14 (1–2): 130–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428x.2017.1420849.

Gorman, Kaitlyn R., Jillian C. Shipherd, Kathleen M. Collins, Hamish A. Gunn, Rachel O. Rubin, Brian A. Rood, and David W. Pantalone. 2020. “Coping, Resilience, and Social Support Among Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals Experiencing Gender-Related Stress.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 9 (1): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000455.

Green, Erica L., Katie Brenner, and Robert Pear. 2018. “‘Transgender’ Could Be Defined Out of Existence Under Trump Administration.” The New York Times, October 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/21/us/politics/transgender-trump-administration-sex-definition.html.

Haider-Markel, Donald, Jami Taylor, Andrew Flores, Daniel Lewis, Patrick Miller, and Barry Tadlock. 2019. “Morality Politics and New Research on Transgender Politics and Public Policy.” The Forum 17 (1): 159–81. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2019-0004.

Hatzenbuehler, Mark L. 2009. “How Does Sexual Minority Stigma ‘Get Under the Skin’? A Psychological Mediation Framework.” Psychological Bulletin 135 (5): 707–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016441.

Hatzenbuehler, Mark L. 2017. “The Influence of State Laws on the Mental Health of Sexual Minority Youth.” JAMA Pediatrics 171 (4): 322. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.4732.

Hatzenbuehler, Mark L., and Katie A. McLaughlin. 2014. “Structural Stigma and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis Reactivity in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Young Adults.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 47 (1): 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9556-9.

Hatzenbuehler, Mark L., Katie A. McLaughlin, Katherine M. Keyes, and Deborah S. Hasin. 2011. “The Impact of Institutional Discrimination on Psychiatric Disorders in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: A Prospective Study.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (3): 452–59. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.168815.

Hendricks, Michael L., and Rylan J. Testa. 2012. “A Conceptual Framework for Clinical Work with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients: An Adaptation of the Minority Stress Model.” Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 43 (5): 460–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029597.

Hughto, Jaclyn M. W., David J. Meyers, Matthew J. Mimiaga, Sari L. Reisner, and Sean Cahill. 2021. “Uncertainty and Confusion Regarding Transgender Non-Discrimination Policies: Implications for the Mental Health of Transgender Americans.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00602-w.

Hughto, Jaclyn M. White, Sari L. Reisner, and John E. Pachankis. 2015. “Transgender Stigma and Health: A Critical Review of Stigma Determinants, Mechanisms, and Interventions.” Social Science & Medicine 147: 222–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010.

James, Sandy, Jody Herman, Susan Rankin, Mara Keisling, Lisa Mottet, and Ma’ayan Anafi. 2016. The Report of the 2015 US Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality.

Kenagy, G P. 2005. “Transgender Health: Findings from Two Needs Assessment Studies in Philadelphia.” Health & Social Work 30 (1): 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/30.1.19.

King, Wesley M., Jaclyn M.W. Hughto, and Don Operario. 2020. “Transgender Stigma: A Critical Scoping Review of Definitions, Domains, and Measures Used in Empirical Research.” Social Science & Medicine 250: 112867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112867.

Kteily, Nour, and Emile Bruneau. 2016. “Backlash: The Politics and Real-World Consequences of Minority Group Dehumanization.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 43 (1): 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216675334.

Kuper, Laura E., M. Brett Cooper, and Megan A. Mooney. 2022. “Supporting and Advocating for Transgender and Gender Diverse Youth and Their Families Within the Sociopolitical Context of Widespread Discriminatory Legislation and Policies.” Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology 10 (3): 336–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpp0000456.

Link, Bruce G., and Jo Phelan. 2014. “Stigma Power.” Social Science & Medicine 103: 24–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.07.035.

Link, Bruce G., and Jo C. Phelan. 2001. “Conceptualizing Stigma.” Annual Review of Sociology 27 (1): 363–85. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363.

Link, Bruce G, and Jo C Phelan. 2006. “Stigma and Its Public Health Implications.” The Lancet 367 (9509): 528–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68184-1.

Matsuno, Em, Nat L. Bricker, Elizabeth Savarese, Roger Mohr, and Kimberly F. Balsam. 2022. “‘The Default Is Just Going to Be Getting Misgendered’: Minority Stress Experiences Among Nonbinary Adults.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000607.

McManus, Hannah D., Francis T. Cullen, Cheryl Lero Jonson, Alexander L. Burton, and Velmer S. Burton Jr. 2019. “Will Black Lives Matter to the Police? African Americans’ Concerns about Trump’s Presidency.” Victims & Offenders 14 (8): 1040–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2019.1671288.

Meyer, Ilan H. 2003. “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence.” Psychological Bulletin 129 (5): 674–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Meyer, Ilan H. 2013. “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 1 (S): 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/2329-0382.1.s.3.

Miller, Patrick R., Andrew R. Flores, Donald P. Haider-Markel, Daniel C. Lewis, Barry L. Tadlock, and Jami K. Taylor. 2017. “Transgender Politics as Body Politics: Effects of Disgust Sensitivity and Authoritarianism on Transgender Rights Attitudes.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 5 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2016.1260482.

Price, Sarah F., Jae Puckett, and Richard Mocarski. 2021. “The Impact of the 2016 US Presidential Elections on Transgender and Gender Diverse People.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 18 (4): 1094–1103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00513-2.

Movement Advancement Project. 2022. “Equality Maps: Snapshot: LGBTQ Equality By State.” Movement Advancement Project. 2022. https://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps.

Puckett, Jae A., Alix B. Aboussouan, Allura L. Ralston, Brian Mustanski & Michael E. Newcomb, and Michael E. Newcomb. 2021. “Systems of Cissexism and the Daily Production of Stress for Transgender and Gender Diverse People.” International Journal of Transgender Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2021.1937437.

Puckett, Jae A., T. Zachary Huit, Debra A. Hope, Richard Mocarski, Brenna R. Lash, Tian Walker, Natalie Holt, et al. 2022b. “Transgender and Gender-Diverse People’s Experiences of Minority Stress, Mental Health, and Resilience in Relation to Perceptions of Sociopolitical Contexts.” Transgender Health. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2022.0047.

Puckett, Jae A., Meredith R. Maroney, Lauren P. Wadsworth, Brian Mustanski, and Michael E. Newcomb. 2020. “Coping with Discrimination: The Insidious Effects of Gender Minority Stigma on Depression and Anxiety in Transgender Individuals.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 76 (1): 176–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22865.

Puckett, Jae A., Emmie Matsuno, Christina Dyar, Brian Mustanski, and Michael E. Newcomb. 2019. “Mental Health and Resilience in Transgender Individuals: What Type of Support Makes a Difference?” Journal of Family Psychology 33 (8): 954–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000561.

Puckett, Jae A., Sarah F. Price, Richard Mocarski, Brian Mustanski, and Michael E. Newcomb. 2022a. “Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals’ Daily Experiences of Rumination.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 92 (5): 540–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000636.

Ralston, Allura L., Natalie R. Holt, Arthur R. Andrews, T. Zachary Huit, Jae A. Puckett, Nathan Woodruff, Richard Mocarski, and Debra A. Hope. 2022. “Mental Health and Marginalization Stress in Transgender and Gender Diverse Adults: Differences Between Urban and Non-Urban Experiences.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000595.

Riggle, Ellen D. B., Sharon S. Rostosky, Laurie Drabble, Cindy B. Veldhuis, and Tonda L. Hughes. 2018. “Sexual Minority Women’s and Gender-Diverse Individuals’ Hope and Empowerment Responses to the 2016 Presidential Election.” Journal of GLBT Family Studies 14 (1–2): 152–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428x.2017.1420853.

Rood, Brian A., Sari L. Reisner, Jae A. Puckett, Francisco I. Surace, Ariel K. Berman, and David W. Pantalone. 2017. “Internalized Transphobia: Exploring Perceptions of Social Messages in Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Adults.” International Journal of Transgenderism 18 (4): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1329048.

Rood, Brian A., Sari L. Reisner, Francisco I. Surace, Jae A. Puckett, Meredith R. Maroney, and David W. Pantalone. 2016. “Expecting Rejection: Understanding the Minority Stress Experiences of Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Individuals.” Transgender Health 1 (1): 151–64. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0012.

Russell, Glenda M., Janis S. Bohan, Marya C. McCarroll, and Nathan G. Smith. 2011. “Trauma, Recovery, and Community: Perspectives on the Long-Term Impact of Anti-LGBT Politics.” Traumatology 17 (2): 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765610362799.

Serano, J. 2016. Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity. Berkeley: Seal Press.

Smart, Benjamin D., Lilli Mann-Jackson, Jorge Alonzo, Amanda E. Tanner, Manuel Garcia, Lucero Refugio Aviles, and Scott D. Rhodes. 2022. “Transgender Women of Color in the U.S. South: A Qualitative Study of Social Determinants of Health and Healthcare Perspectives.” International Journal of Transgender Health 23 (1–2): 164–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2020.1848691.

Stone, Amy L., Elizabeth A. Nimmons, Robert Salcido, and Phillip W. Schnarrs. 2020. “‘Multiplicity, Race, and Resilience: Transgender and Non‐Binary People Building Community.’” Sociological Inquiry 90 (2): 226–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12341.

Tebbe, Elliot A., Melissa Simone, Emily Wilson, and Madeline Hunsicker. 2022. “A Dangerous Visibility: Moderating Effects of Antitrans Legislative Efforts on Trans and Gender-Diverse Mental Health.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 9 (3): 259–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000481.

Vanaman, Matthew E., and Hanah A. Chapman. 2020. “Disgust and Disgust-Driven Moral Concerns Predict Support for Restrictions on Transgender Bathroom Access.” Politics & Life Sciences 39 (2): 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/pls.2020.20.

Veldhuis, Cindy B., Laurie Drabble, Ellen D. B. Riggle, Angie R. Wootton, and Tonda L. Hughes. 2018. “‘We Won’t Go Back into the Closet Now Without One Hell of a Fight’: Effects of the 2016 Presidential Election on Sexual Minority Women’s and Gender Minorities’ Stigma-Related Concerns.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 15 (1): 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-017-0305-x.

Warren-Gordon, Kiesha, and Gayle Rhineberger. 2021. “The ‘Trump Effect’ on Hate Crime Reporting: Media Coverage before and after the 2016 Presidential Election.” Journal of Ethnicity in Criminal Justice 19 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377938.2021.1895944.

Xavier, Jessica, Julie A Honnold, and Judith Bradford. 2007. The Health, Health Related Needs, and Lifecourse Experiences of Transgender Virginians. Richmond: Virginia Department of Health.